Here’s one of the biggest surprises of 2015 for me: one of the organizations best reflecting the American people is the NARAS. The five nominees for the Album of the Year Grammy each come from a different genre: pop, rock, rap, country, and the blend of soul and electronica that Abel Tesfaye creates. Moreover, for the first time in the three years I have written this round-up, every nominee topped the Billboard album charts. What you’re about to read is truly populist representation. You might agree it’s among the best of the world’s music. You also might find some of it pandering, annoying, or unlistenable. Me, I would have added Florence + The Machine, Father John Misty, and the first bootleg of the Grateful Dead’s Soldier Field shows—but who wants to carry the mantle of American taste on their shoulders?

That said, comments welcome!

Alabama Shakes has a sound like a lo-fi, slowed down mixture of Led Zeppelin and late Motown, all thudding rumbles and blues-rock riffing drifting out of our speakers as if it was a distant sound heard from a window. Sound & Color is forty-seven minutes of these sounds passing by in a haze, creating a mellow, almost druggy atmosphere, waking up only on a few uptempo tracks and the fun, unexpected jam in “Gimme All Your Love.” There are few memorable melodies, and since the tone quickly begins to wear, Sound & Color would be unremarkable except for lead singer/chief songwriter Brittany Howard. Howard has a voice without equal: one could compare her to Nina Simone or one of the British or Australian heavy metal singers and the analogy would be understandable but wrong in either case: her vocals combine a light, heartfelt, jazzy quality (which dominates the title track) with a ferociousness (which dominates “Shoegaze”). Both sides combine on the album’s smattering of standouts: “Don’t Wanna Fight,” a song which in its lockstep rhythm and Howard’s passion portrays the stresses of low-income millennial love to a tee, the soaring “Dunes,” and the closing “Over My Head,” whose romantic rhythms make up for the penultimate, overlong “Gemini.”

Alabama Shakes has a sound like a lo-fi, slowed down mixture of Led Zeppelin and late Motown, all thudding rumbles and blues-rock riffing drifting out of our speakers as if it was a distant sound heard from a window. Sound & Color is forty-seven minutes of these sounds passing by in a haze, creating a mellow, almost druggy atmosphere, waking up only on a few uptempo tracks and the fun, unexpected jam in “Gimme All Your Love.” There are few memorable melodies, and since the tone quickly begins to wear, Sound & Color would be unremarkable except for lead singer/chief songwriter Brittany Howard. Howard has a voice without equal: one could compare her to Nina Simone or one of the British or Australian heavy metal singers and the analogy would be understandable but wrong in either case: her vocals combine a light, heartfelt, jazzy quality (which dominates the title track) with a ferociousness (which dominates “Shoegaze”). Both sides combine on the album’s smattering of standouts: “Don’t Wanna Fight,” a song which in its lockstep rhythm and Howard’s passion portrays the stresses of low-income millennial love to a tee, the soaring “Dunes,” and the closing “Over My Head,” whose romantic rhythms make up for the penultimate, overlong “Gemini.”

Back in April, I reviewed To Pimp a Butterfly by Kendrick Lamar and described it as the record that “cements him as one of the most vital forces in American music.” Now, as this turbulent year draws to a close, a re-listen only maximizes the force of Lamar’s dynamic confrontation of racism, violence, abusive sex, and the inner struggles within us. The poetry feels darker, and now comes across as more reflective than ever of this nation’s ugliness: “These Walls” and “The Blacker the Berry” are the sounds of impending psychological doom and a death that will matter to no one. But a re-listen also brings out the beauty and catchiness of the jazz-soul backdrops that support Lamar while never overpowering him, while “Alright” and “i” take their place as optimistic calls to action. One thing I was wrong about: after spending so much time reading the words of people from Ta-Nehisi Coates to the Black Lives Matter figureheads, “Mortal Man” is a perfect closer, the orchestrated funk fading into the ether while Lamar and 2Pac’s imaginary conversation represents a need to pull strength from the past while building the finest present and future we can.

Back in April, I reviewed To Pimp a Butterfly by Kendrick Lamar and described it as the record that “cements him as one of the most vital forces in American music.” Now, as this turbulent year draws to a close, a re-listen only maximizes the force of Lamar’s dynamic confrontation of racism, violence, abusive sex, and the inner struggles within us. The poetry feels darker, and now comes across as more reflective than ever of this nation’s ugliness: “These Walls” and “The Blacker the Berry” are the sounds of impending psychological doom and a death that will matter to no one. But a re-listen also brings out the beauty and catchiness of the jazz-soul backdrops that support Lamar while never overpowering him, while “Alright” and “i” take their place as optimistic calls to action. One thing I was wrong about: after spending so much time reading the words of people from Ta-Nehisi Coates to the Black Lives Matter figureheads, “Mortal Man” is a perfect closer, the orchestrated funk fading into the ether while Lamar and 2Pac’s imaginary conversation represents a need to pull strength from the past while building the finest present and future we can.

Mostly, Butterfly remains one of the greatest records of our time, and Kendrick Lamar is “by far, realest Negus alive.”

Chris Stapleton, the most unfamiliar name on this list, took his first album to number one at age 37. Stapleton is a veteran country songwriter who’s written smash hits for Kenny Chesney and Luke Bryan among many others, but Traveler has nothing to do with their sounds. This is an album of stripped-down tales of women, God, whiskey, and wandering with enough Southern to burst an amplifier. Stapleton plays a soulful guitar and mandolin, with a crack sextet anchored by pianist Michael Webb and Morgane Hayes (Mrs. Stapleton) on harmony vocals, and sings with an endearing roughness. There is nothing new here in terms of musical style or lyrical themes, but Stapleton’s commitment to the country tradition produces several gems: the rocking “Parachute,” the uplifting “When the Stars Come Out,” and one of the finest drinking songs of our time, “Whiskey and You.” However, this record gets marked down a touch because while designed to showcase Stapleton performing his own songs, the apex of Traveler is its two covers: the driving version of Charlie Daniels’s “Was It 26” and the surprise hit, David Allan Coe’s “Tennessee Whiskey,” a smooth, enchanting piece that turns Jack Daniel’s into something mystical.

Chris Stapleton, the most unfamiliar name on this list, took his first album to number one at age 37. Stapleton is a veteran country songwriter who’s written smash hits for Kenny Chesney and Luke Bryan among many others, but Traveler has nothing to do with their sounds. This is an album of stripped-down tales of women, God, whiskey, and wandering with enough Southern to burst an amplifier. Stapleton plays a soulful guitar and mandolin, with a crack sextet anchored by pianist Michael Webb and Morgane Hayes (Mrs. Stapleton) on harmony vocals, and sings with an endearing roughness. There is nothing new here in terms of musical style or lyrical themes, but Stapleton’s commitment to the country tradition produces several gems: the rocking “Parachute,” the uplifting “When the Stars Come Out,” and one of the finest drinking songs of our time, “Whiskey and You.” However, this record gets marked down a touch because while designed to showcase Stapleton performing his own songs, the apex of Traveler is its two covers: the driving version of Charlie Daniels’s “Was It 26” and the surprise hit, David Allan Coe’s “Tennessee Whiskey,” a smooth, enchanting piece that turns Jack Daniel’s into something mystical.

1989 is now permanently imprinted in my brain, and the ultimate conclusion I draw about the biggest-selling album of the year is that beyond the pastiche of 1980s pop and a bit of her co-producer Max Martin’s compatriots ABBA, Taylor Swift made a record full of sadness below its exuberant surface. 1989 is ultimately a break-up album, a category whose appropriateness is reiterated by her monologues and presentation in her live show and Ryan Adams’s entrancing interpretation, and as such there is much about it that’s not fun. This sadness is in the starkness of “Blank Space,” the dark underpinnings of “Style,” the melodramatic epic scale of the songs written with Jack Antonoff, and the paranoia of “I Know Places.” Even “Shake It Off” takes on a new tone when one combines an optimism that protests too much with Swift’s admission in the liner notes that it’s a song about dancing to forget your heartache. Catharsis only arrives in the end with “Clean,” which mixes the deliberately simple Imogen Heap arrangement with terrific lyrics that declare Swift is leaving her pain behind for a more mature life. The album should live on as a near-perfect pop record and essential listening for the lovelorn. (Although the original “How You Get the Girl” is still flat.)

1989 is now permanently imprinted in my brain, and the ultimate conclusion I draw about the biggest-selling album of the year is that beyond the pastiche of 1980s pop and a bit of her co-producer Max Martin’s compatriots ABBA, Taylor Swift made a record full of sadness below its exuberant surface. 1989 is ultimately a break-up album, a category whose appropriateness is reiterated by her monologues and presentation in her live show and Ryan Adams’s entrancing interpretation, and as such there is much about it that’s not fun. This sadness is in the starkness of “Blank Space,” the dark underpinnings of “Style,” the melodramatic epic scale of the songs written with Jack Antonoff, and the paranoia of “I Know Places.” Even “Shake It Off” takes on a new tone when one combines an optimism that protests too much with Swift’s admission in the liner notes that it’s a song about dancing to forget your heartache. Catharsis only arrives in the end with “Clean,” which mixes the deliberately simple Imogen Heap arrangement with terrific lyrics that declare Swift is leaving her pain behind for a more mature life. The album should live on as a near-perfect pop record and essential listening for the lovelorn. (Although the original “How You Get the Girl” is still flat.)

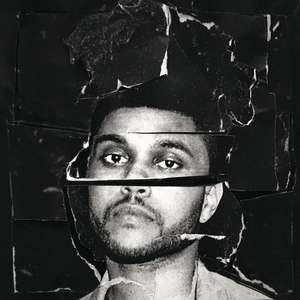

The Weeknd’s music, at least that on Beauty Behind the Madness, is a study in contradictions. His singing voice is a sterling cousin of Michael Jackson’s, full of range and never missing a note, and set against a backdrop of smart, moving electronica. These vocals, though, sing of a well-mixed combination of beauty and madness, mixing a deeply sensual, romantic vibe with disturbing lyrical concepts. The prime example is the most MJ-recalling cut, “In the Night,” which is so perfectly structured that it could have been the tenth song on Thriller, but narrates a tale of a woman who was sexually abused as a child. All of the album’s biggest hits touch on dark themes: “The Hills” is an infectious tale of infidelity, “Can’t Feel My Face” is a drug addiction metaphor, albeit with the wonderfully hook-laden “She don’t need to worry” bridge, and “Earned It (Fifty Shades of Grey)” is self-explanatory. These are all very good pop songs, even though the otherwise ideal make-out number “Earned It” rhymes “unexpected” and “expected.”

The Weeknd’s music, at least that on Beauty Behind the Madness, is a study in contradictions. His singing voice is a sterling cousin of Michael Jackson’s, full of range and never missing a note, and set against a backdrop of smart, moving electronica. These vocals, though, sing of a well-mixed combination of beauty and madness, mixing a deeply sensual, romantic vibe with disturbing lyrical concepts. The prime example is the most MJ-recalling cut, “In the Night,” which is so perfectly structured that it could have been the tenth song on Thriller, but narrates a tale of a woman who was sexually abused as a child. All of the album’s biggest hits touch on dark themes: “The Hills” is an infectious tale of infidelity, “Can’t Feel My Face” is a drug addiction metaphor, albeit with the wonderfully hook-laden “She don’t need to worry” bridge, and “Earned It (Fifty Shades of Grey)” is self-explanatory. These are all very good pop songs, even though the otherwise ideal make-out number “Earned It” rhymes “unexpected” and “expected.”

This is the worst since Steve Miller rhymed “Texas,” “facts is,” “justice,” and “taxes.”

The album itself is good on the whole. Four or five songs sound far too similar and drag the work down, but there are some standout cuts that haven’t gotten radio play, including the terrific opening shot of “Real Life” and “Losers” and two duets at the end, “Dark Times,” on which The Weeknd and Ed Sheeran from a depressing Rat Pack, and “Prisoner,” which pairs the Canadian crooner with Lana Del Rey, one of the only artists who surpasses his macabre side.

The Verdict

This year, I would recommend all these albums (although Sound & Color requires the right mood), but To Pimp a Butterfly and 1989 are in a higher class. I would be hard-pressed to choose between Lamar’s stirring virtuosity and Swift’s mastering of the pop songwriting world. I’d imagine the trophy will go to Swift, whose massive sales are harder to ignore than ever in the modern musical landscape, and I applaud that decision, but Lamar’s document of the 2010s is the greater achievement.

I believe both records will live on as long as people listen to music, which is the finest reward of all.

Photos from The Source and Wikipedia.