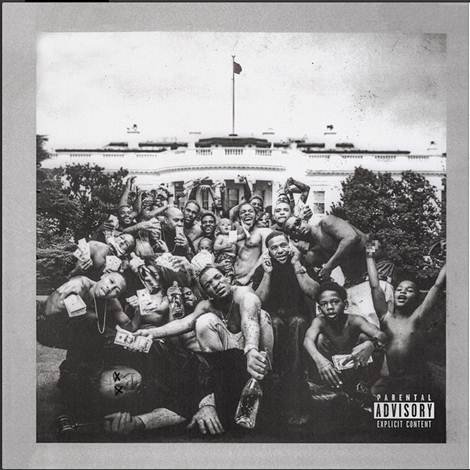

27 year-old Kendrick Lamar’s first major-label LP, good kid, m.A.A.d. city, was one of the best albums of recent memory (in my opinion). Lamar’s poetic gifts blended perfectly with an ultra-minimalist backdrop appropriate to his complex tale of gangs, struggle, and redemption in Compton. On To Pimp a Butterfly, the lyrics are still the same superb quality, but the music has gotten larger to match a concept that demands even more attention and asks more demanding questions.

An Elaborate Maelstrom

This time, Lamar’s stylistic palette obliterates good kid’s bass/drum/synth line aesthetic to incorporate funk arrangements that demands you get up and dance, giant-sounding tunes reminiscent of classic soul, and even jazz—some of the best tracks are simply Lamar reciting poetry over bebop runs of which Bird, Diz, and Monk would have thoroughly approved. Helping the record along are variety of people, from his peers Thundercat, Rapsody, Bilal, Anna Wise, to elder statesmen Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, and Ronald Isley, to the ubiquitous Pharrell Williams. The elaborate variety of music draws a listener in, but the message of the lyrics is what makes one stay.

For success clearly has not sat well with Lamar. The album’s title is a reflection of how society exploits and destroys people trying to make art, affect change, and break free from the status quo—especially when those people are black. Half of the record consists of Lamar roaring at the artistic, financial, sexual, and violent temptations that only destroy. On good kid this temptation was personified by the passionate figure of Sherane, but now Lamar gives us Lucy, the continually beckoning forces of Hell. However, this is not a simple protest record and there is no self-aggrandizing, for the other half of Butterfly is Lamar roaring at himself, castigating his own weaknesses and failings and dwelling in guilt for finding success while so many are still stuck in their own Comptons. This side is exemplified in “u,” a chillingly recognizable maelstrom of self-hatred, of all the darkest things we think about ourselves spoken out loud.

Lamar’s negotiation of what problems are his, what problems are social, and how he can solve those problems is obviously not an easy one, and Butterfly swings back and forth between confidence (the defiant, funky explosion of “King Kunta”) and grimness (“How Much a Dollar Cost,” a tale of an encounter with a homeless man that becomes a work of high drama), and sometimes both in the same song, notably on “These Walls,” on the surface a quiet storm number, but one that switches from rejoicing in sex to lamenting the pain Lamar has inflicted on others.

The Finale and the Solution

To Pimp a Butterfly closes with an unforgettable stretch of songs which find Lamar reaching a breaking point and finding resolution…though resolution does not come until after the nightmarish “The Blacker the Berry,” five minutes of raging against white America and the society that led to the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Eric Garner, all set to one of the most danceable beats on the record. Then in the final lyric, Lamar turns the anger on himself for participating in gang wars where black men killed other black men for having darker skin. This devastating cycle of destroying each other, Lamar implies, goes beyond race and affects everyone in the end, offering no easy answers.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6AhXSoKa8xw

Until Lamar finds an answer. Throughout To Pimp a Butterfly, Lamar repeats and expands upon a description of the pressures swirling inside him, a description he seems to be addressing to one person. In the closing “Mortal Man,” a powerfully melodic song inspired by Lamar’s visit to Robben Island and seeing Nelson Mandela’s prison, Lamar reveals he is speaking to his idol, Tupac Shakur. The two have a long conversation (using edited clips of a 1994 Shakur interview) about the need to be principled and to teach others that beauty, strength, and change can come from even the worst circumstances.

In between these two songs, we are given the inspirational, positive gift of “i.” Set to the propulsive beat of the Isley Brother’s “That Lady,” Lamar tells the world that there is bad inside all of us, but there is also good, and accepting this leads to a sense of self-love and self-worth, and from there the energy to do good in the world. In the gorgeous finale (and my only complaint about this record is that “i” feels like an even more natural send-off than “Mortal Man”), Lamar raps a capella, pays a surprising tribute to Oprah Winfrey, and rejects the “n” word for “negus,” the Ethiopian term for royalty. “Say it with me or say no more,” he urges the listener.

In Summation

To Pimp a Butterfly is a confrontational listen, and a very painful one, but it finishes in revelation and triumph, and cements Kendrick Lamar as one of the most vital forces in American music. Not all of us have gone through the particular life experience Lamar did, but all of us certainly have dealt with the turmoil of trying to figure out if we’re achieving what we truly need in life and trying, in the role of our own harshest critics, to forgive ourselves. Lamar has given us a gift in documenting this turmoil in such a relatable way, and the multitude of hooks is simply a bonus.

Photographs from All About HipHop and The Guardian