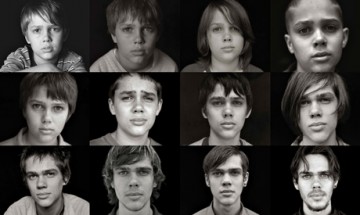

It’s like seeing your life flash right by. (Image via.)

Boyhood has been the indie hit of the summer. It has broken out commercially to the tune of $20 million through its first nine weeks of release and received a rare perfect 100 score on the review aggregator Metacritic. After weeks of dithering I finally made time to see the film on Labor Day and can safely say the hype is justified. Boyhood is guaranteed to be among the best films of the year and is a singular achievement in cinematic history.

Poster of the year. (Image via.)

Perhaps the Longest Production in Cinema History

You’ve probably seen a headline about Boyhood since it debuted at the Sundance Film Festival in January and for good reason. Director Richard Linklater, whose Before series indicates a certain fondness for large-scale passion projects, shot the movie over the course of 11 years. He had long wanted to film a movie about the experience of growing up and how parent-child relationships change over time. He has stated in interviews that such a project was too large to pull off convincingly in one go, since so much of the experience that is maturation is dependent on circumstance.

So Linklater got IFC to put up $200,000 so that the film could shoot for a few weeks every year from 2002 to 2013. The cast included an unknown 7-year-old in the lead role of Mason, Jr., Linklater’s own daughter as the older sister Samantha, and longtime Linklater collaborators Ethan Hawke and Patricia Arquette as their estranged parents. Every member of the cast contributed to writing the film, and the arc of these character’s lives was allowed to grow and change over the decade-spanning shoot.

At 17 I wanted my hair to look like this. At 27 I think it would just be nice to have hair. (Image via.)

A Movie of Particular Details and Universal Insights

The effect of that singular production is startling while watching Boyhood. The narrative begins when Mason, Jr. is six years old in 2002. Britney Spears’ tawdry bubblegum pop is sung by girls far too young to understand its connotations. Sheryl Crowe’s “Soak Up the Sun” blares out of every speaker in existence. Patricia Arquette’s Olivia is dressed in the swishy Adidas pants and cotton tank top that was the uniform of harried suburban moms everywhere. It’s like watching a crash course in what defined 2002 in popular culture. Every year that the film skips through feels similarly familiar. Because Linklater filmed over a continuous period, it afforded him the luxury of living in the cultural moment. Movies about young people are often caught in the trap of nostalgia, as creators look back on their own past for the setting of such stories. For example, Linklater’s own Dazed and Confused and Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous are both great movies, but they share this reverse-engineered quality.

Within the cultural particulars that Mason experiences, the film keeps its focus small and its stakes low. Linklater transparently aimed to make a story entirely missing any melodramatic sizzle. Instead, we see moments like Mason silently digging a grave for a bird by himself as a 6-year-old or worrying that the buzzcut one of his stepfathers foists upon him will invite ridicule at school. To be certain, there are bigger arcs that guide us along and shape Mason’s life. His mom struggles with money and marries two different men who turn out to be the wrong fit for her family. His dad is a classic helicopter parent, zooming in every other week for camping trips and late night hang-outs. He’s a consistent source of joy for both his kids, but Mason’s father only rarely has to deal with the daily rigors of disappointment and disaffection that constant parenting engenders.

Star Ellar Coltrane and director Richard Linklater. This movie will define both their careers. (Image via.)

What makes all of this work is that the focus is kept on Mason without ever putting him through a ringer. He grows into an introspective and artistic young man across the nearly three-hour running time, but the film shows us that without the building progress and climactic self-actualization that mark the traditional Bildungsroman. Instead, the film breathes and grows around him by not being a dirge of self-aware & “Important” moments. Big life events like his parent’s marital status changing, various moves around Texas, first kisses, and later first sexual experiences are elided around. By skipping past the typical Hollywood cause-and-effect plotting or goal-oriented characterization the audience is left with a sensation of dropping in on a life while it’s lived. We can fathom the changes in Mason and his environment because they are drawn with precision and grace, not because of exposition. By the end of the film it felt like Mason was someone I had known for years and just didn’t see very often. Honestly, I probably know him better than I do many of my cousins or friends.

The best proof of this is probably in the audience going to see Boyhood. When I took in the film at Chicago’s Landmark Cinemas it was mainly with with middle-aged & elderly couples. Their own childhood experiences could not have included playing Halo 2. But scenes like Mason getting dressed down by his boss for flirting while at work can strike a chord with almost any viewer. Boyhood is Mason’s story, but his is the story of growth, discovery, boredom, disaffection, and wonder that all young people go through. I’ve never seen it captured more naturally on screen before. Neither has anyone else for that matter.