Andrew: Annie Clark and Andrea Pino had two things in common when they met. One, they were very proud students of the University of North Carolina. Two, they had been raped on campus. Their accusers were never punished. And when they took a stand against UNC’s handling of the situation, the school’s chief legal counsel, a woman, emphatically declared they were completely wrong.

Andrew: Annie Clark and Andrea Pino had two things in common when they met. One, they were very proud students of the University of North Carolina. Two, they had been raped on campus. Their accusers were never punished. And when they took a stand against UNC’s handling of the situation, the school’s chief legal counsel, a woman, emphatically declared they were completely wrong.

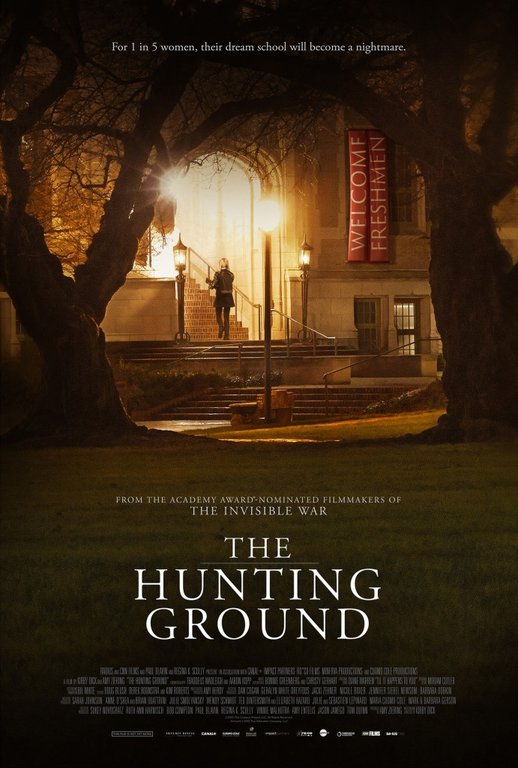

This story is that it is all too common across America, and this epidemic of sexual assault and institutional misogyny in our colleges is the subject of two-time Oscar nominee Kirby Dick’s new documentary, The Hunting Ground, which, for several reasons, is one of the most heartbreaking and important films to come out this decade.

A Bitter Universality

Andrew: Dick and his producing partner Amy Ziering build an unimpeachable case that rape and failure to justly deal with it are major issues in higher education. The film contains many interviews with psychologists, sociologists, and college administrators, and is peppered with statistics from various research papers–one of the most shocking being that schools such as UNC, Stanford, and Dartmouth have never expelled students for rape in the past decade, while hundreds have been tossed for violating academic honor codes.

However, no one could mistake The Hunting Ground as a dry presentation of facts. The film’s power comes from having more women than I could count who suffered sexual assault tell their stories on camera. It quickly becomes clear that, given how one in five women are raped on college campuses, Dick and Ziering were sadly not going to run out of subjects.

Gina: I think you could talk to any woman who’s attended college in the last thirty years, and if she was not the victim of a sexual assault, then she most likely had at least a close call or two. During our college years, women don’t walk around in constant terror, but there is a sort of low-grade hum that vibrates in the back of your mind. Any time you’re at a party, out with a guy, in a bar, walking home at night, visiting a friend’s dorm, or countless other typical college activities, you are constantly doing a threat assessment. It’s not white-knuckle panic 24/7, but such vigilance takes a toll. It’s a demand on our energy and mental capacity that (most) men never have to experience. It’s like that infamous quote about how Ginger Rogers had to do everything Fred Astaire did, but she had to do it backward and in high heels. During our college years, when we are forming our worldview, expanding our minds, learning, growing, and becoming ourselves, young women shouldn’t have to worry that if we are raped, we will be asked what we were wearing or how much we had to drink instead of being provided with the help, advocacy and justice that should be our right.

Andrew: There were two instances early on that echo what Gina says completely and wrenched my soul. Several of Dick’s interviewees are intelligent, spirited women who ultimately dropped out of their schools in the wake of their experiences, or worse; one long interview is with the father of a girl who committed suicide after it became clear that Notre Dame would not act against the football player who raped her. But on a more personal level, another sequence deals with a Harvard Law student who got the classmate that assaulted her and her best friend expelled, only to find him readmitted the next semester. While she retold her story, the film showed streets in Boston and Cambridge that I myself had walked on many a time in my college days. It struck me like a sixteen-ton weight that I had never once paid any mind to that low-grade hum Gina spoke of, nor had I ever given any thought to the likelihood that a friend of mine may have been one of those terribly hurt, and the realization of gender privilege has left me with shame.

Three Endings and a Definition

Andrew: Not a long film at 103 minutes, The Hunting Ground finishes with a three-part ending. Dick saves his most dramatic short story for last, as he speaks to Erica Kinsman, who accused Jameis Winston of raping her. Lab tests identified Winston as her assailant, but the case was never properly investigated, Winston was never charged, and Florida State refused to discipline their Heisman-winning quarterback. Kinsman was vilified and even called out on ESPN (by Skip Bayless) for attacking such an “outstanding young man” at the height of football season. Even if there had been more ambiguity in the situation, Kinsman’s story reveals how rape victims suffer far more blame and condemnation, especially from the institutions meant to protect them, than the rapists themselves.

The film then switches to a scene of triumph and hope. Annie Clark and Andrea Pino, who became close friends and housemates, did their research, filed a Title IX complaint against UNC, and devoted themselves to connecting with other victims across the country and teaching them how to advocate for truly effective policies against sexual assault. Their efforts led to over seventy complaints filed, meetings on Capitol Hill, and a call to action from President Obama. In She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry, the early feminist leaders praised the power of women talking about shared experiences as the catalyst for social change; Clark and Pino carry that spirit forward.

Then in the final shots, the movie’s aim becomes clear. Title cards starkly state that if nothing changes, 100,000 more rapes will occur in college campuses next year, and then provide resources for how people can take action.

The Hunting Ground, you see, is not a documentary in the tradition of the Maysles and Frederick Wiseman, nor is it like Tony Kaye’s extraordinary Lake of Fire, which somehow managed to not play favorites in giving pro-life and pro-choice activists equal say. The Hunting Ground is a polemic with a clear sense of right and wrong. Some critics, including the New York Times‘s Manhola Dargis, critiqued the movie for not showing the other side’s story. But Gina and I had to wonder who exactly is the other side.

Gina: This film is 100% a polemic. It is a documentary, but it’s not journalism. There is nothing objective about this film. It is activism, plain and simple, but I have no problem with that. I think other very powerful films are also activism (i.e. An Inconvenient Truth). Objective journalism is essential in many contexts, but with an issue like this, there simply is no “other side” of the story. We as the audience, and those of us critiquing this film, can certainly parse out how the filmmakers make their case and how well (or how poorly) they do so, but no such assessment changes anything about the facts.

To continue with the An Inconvenient Truth analogy: yes, you can split hairs about the science presented in the film, you can criticize how the information is presented, you can claim it sensationalizes and pulls at the heartstrings, and cherry-picks data, and all of that. But it doesn’t change the fact that global warming is a very real and very dangerous problem. The same can be said for The Hunting Ground. Pull it apart the presentation all you want, but it doesn’t mean there isn’t a real problem underneath. And if there is an “other side” of the issue, how much do we even need to listen to it? Climate change deniers, rape deniers. It’s all the same to me.

What to Take Away

Andrew: Beyond the clarion call for revolutionary change in how higher education operates for the benefit of its students, there is an even darker undercurrent in The Hunting Ground that points to the breaking point American society approaches. A system designed for growth and free expression of ideas that in practice supports a patriarchal double standard is a system that reinforces masculine freedom and superiority and shatters empathy. The refusal to take rape allegations seriously, the victim-blaming, the dismissal of professors and administrators who speak up for those hurt by sexual assault–it all sends the message that men can act as they wish without consequences. In one chilling moment, during an extended look at SAE and other fraternities (who have a powerful lobbying interest in D.C.), the Greek organizations at UC Berkeley kept a message board of sexual conquests and frequently signed off with Cato’s Latin maxim “Carthage must be destroyed,” but inserting the name of Berkeley’s most outspoken sexual assault advocate in place of Carthage. That such privileged figures operate with near-impunity is brutal.

More importantly, this is a system that weakens and objectifies women, who are still vastly underrepresented in leadership positions in this country and are still at multiple social disadvantages. The culture of our colleges and universities so blatantly declares that women’s rights are not as important as men’s, and in doing so teaches a lesson as important, if not more so, than anything gained in science and economics courses. It is a lesson that needs to be unlearned.

Gina: Rape is not going away as long as humans have free will, but we can do a lot more to protect and advocate for victims and to create a culture less likely to promote sexually aggressive (and essentially punishment-free) behavior. As any rape victim will tell you, the most painful and devastating part of an assault is not the attack itself, but how s/he is treated afterward by those who are supposed to help. No, universities can not stop rape, but they can do much more to reduce it on campuses and to handle accusations when it does occur. My one complaint with the film is that, although it explains a lot about what universities are doing wrong, it doesn’t go far enough to explain what they should be doing instead. Title IX claims are the first step, but beyond that, a federally-mandated (or at least state-by-state) protocol should to be established for handling accusations of sexual assault. If a specific set of standardized steps are in place to allow for due process, then everyone is protected: the school, the victim and the accused.

The government should also mandate better disclosure of assault incidence statistics. If all schools are required to make their crime rates public knowledge, then any one individual school is less likely to balk. Harvard (for example) doesn’t want to put its rape stats out there, because their administration knows that prospective students and their families will see those numbers and think they’d be safer choosing Yale or Princeton instead. But if Harvard, Yale and Princeton are all required to make their stats public, those students and families will understand it is a universal problem, and no one school is more “dangerous” than another.

Also, as the film points out very effectively, it is a small number of men committing a disproportionally large number of assaults as repeat offenders. You would think schools would want to identify these bad apples and expel them. Rape figures would plummet if they did so. They would also plummet if universities stopped shielding the also disproportionately high number of offenders within fraternities and athletic programs.

Finally, I made a point to read a few “negative” reviews of the film to see what is being said, and found that most of the negative press falls into two categories: those that split hairs about the statistics presented, and those that basically defend universities, citing the risks inherent in what can be seen as “he said/she said” accusations. Both of those arguments leave me cold. A false accusation can ruin a person’s life and no one ever wants to see that happen. But the film and other reliable sources make it abundantly clear that false rape claims are relatively rare and are no more prevalent than false reports of any other types of crime.

A lot of the harshest reviews of this film seem to miss the point of The Hunting Ground entirely. The filmmakers, Clark and Pino, and others are not asking that all men accused of assault on college campuses be immediately expelled and/or tossed in jail, which (if you read between the lines) is what a lot of the negative reviews seem to imply. No one is calling for a witch hunt: they simply don’t want to be ignored so that a university can protect itself at the expense of the safety of its student body. They are asking for due process. They are asking for a fair and swift investigation.

They are asking to be heard.

Photographs from The Huffington Post, Ms., and The Raleigh News & Observer. The Hunting Ground is in cinemas and will also be shown on CNN this year.