Andrew Rostan was a film student before he realized that making comics was his horrible destiny, but he’s never shaken his love of cinema. Every two weeks, he’ll opine on either current pictures or important movies from the past.

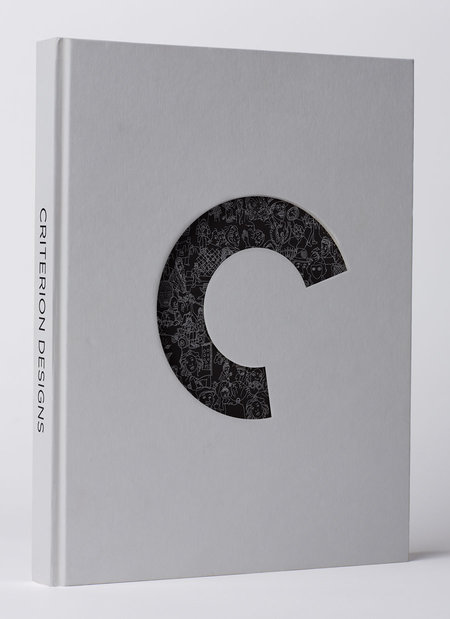

Thirty days before Christmas, one of this year’s best gifts for the film fan will be released. Criterion Designs is a 300-page coffee table book documenting the art of the Criterion Collection. Since 1984, first on laserdisc and now on DVD and Blu-Ray, Criterion has been responsible for reissuing the greatest films ever made in the best possible formats—they popularized letterboxing, restoration, and commentary tracks.

With all this, any fan will tell you that the hallmark of the collection is its design. World-class illustrators and designers work on each new release to create iconic imagery that, minimalist or elaborate, can tell an entire story in a single frame. (Indeed, Criterion art is now so distinctive that many outstanding parody sites have sprung up that give the label’s treatment to much less-deserving films.) The treat of Criterion Designs is in its presentation of sketches and first drafts, culminating in a gallery of every single cover. It’s an art lover’s dream…

That should also serve to make one go out and watch some of the movies. The Criterion Collection’s presentation, for all its aesthetics, is ultimately packaging—but packaging in the best “form serving content” sense. Last week, I wrote about Karina Longworth’s podcast You Must Remember This, and in one episode Longworth discussed how we have so few of the earliest films ever made because producers would simply throw film stock away. The Criterion Collection, in the care it lavishes, is an affirmation that film is not disposable but one of our highest art forms, a dramatic and visual experience like no other that is worth preserving and elevating.

At least, that was the belief Criterion reinforced for me. During my years in Boston and Los Angeles, I sought out the Criterion label first in indie video stores and then on Netflix. Each time I would see a film made at a level I knew I should aspire to reach with my own art. From their first DVD release, Grand Illusion, to their most recent titles, including La Dolce Vita (and why that one took so long is beyond me), Criterion’s selections prove that great movies can be made on a giant budget or none at all, feature superstars or people who’ve never acted, as long as the story speaks to what it means to be human and shows us an ideal to aspire to or tragedy to learn from. The giant-scale Criterion Designs makes all the more sense: films that inspire and stir us deserve the handsomest dressing possible.

Here are five (well, six) particular favorites of mine from the Criterion Collection, all still in print:

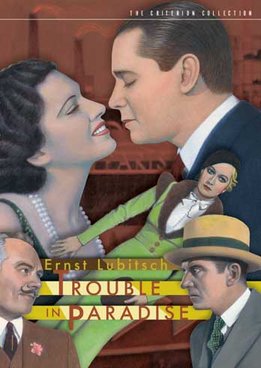

Trouble in Paradise: Filmed in 1932 before the Hays Office began enforcing the censorious Production Code, Ernst Lubitsch’s crowning achievement feels far from old-fashioned but distinctly timeless in its humor, themes, and style. Two con artists try to swindle each other, fall in love, concoct an elaborate scheme against a loopy heiress, and ultimately find that more romance complicates matters. Throughout, Lubitsch is frank about money, sex, and deceit, and the laughs never stop.

Trouble in Paradise: Filmed in 1932 before the Hays Office began enforcing the censorious Production Code, Ernst Lubitsch’s crowning achievement feels far from old-fashioned but distinctly timeless in its humor, themes, and style. Two con artists try to swindle each other, fall in love, concoct an elaborate scheme against a loopy heiress, and ultimately find that more romance complicates matters. Throughout, Lubitsch is frank about money, sex, and deceit, and the laughs never stop.

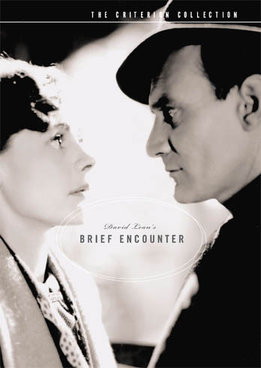

Brief Encounter: Before he gave the world Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago, David Lean received his first international recognition for this tiny, black-and-white movie from 1945. The story by Noel Coward focuses on a housewife and a married doctor who meet by chance in a London train station and fall in love. It’s a film full of shadows, lingering takes, and quiet but intense moments that make us think back to our first love, our deepest moments in love, our heartbreak when a relationship ends. In other words, it’s impossible not to run the emotional gamut.

Brief Encounter: Before he gave the world Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago, David Lean received his first international recognition for this tiny, black-and-white movie from 1945. The story by Noel Coward focuses on a housewife and a married doctor who meet by chance in a London train station and fall in love. It’s a film full of shadows, lingering takes, and quiet but intense moments that make us think back to our first love, our deepest moments in love, our heartbreak when a relationship ends. In other words, it’s impossible not to run the emotional gamut.

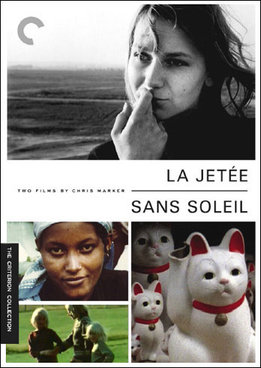

La Jetee/Sans Soleil: Made twenty years apart, these two films (combined on one disc) by French auteur Chris Marker made me completely revaluate both what movies were capable of and how we can tell stories. The former, a 20-minute short from 1962, uses only black-and-white still photographs to tell an epic tale of time travel, apocalypse, and romance with more intelligence and suspense than most Hollywood movies today. (Terry Gilliam remade it as the fascinating but inferior Twelve Monkeys.) The latter is a 1983 documentary in which a woman reads letters from a male acquaintance traveling around the world, primarily a sojourn through Japan. What stimulates is not only the kaleidoscope of word and image, but the spiraling number of narrative levels (author, narrator, their perspectives on other cultures as compared to how those cultures see themselves) that make us question what we know to be true.

La Jetee/Sans Soleil: Made twenty years apart, these two films (combined on one disc) by French auteur Chris Marker made me completely revaluate both what movies were capable of and how we can tell stories. The former, a 20-minute short from 1962, uses only black-and-white still photographs to tell an epic tale of time travel, apocalypse, and romance with more intelligence and suspense than most Hollywood movies today. (Terry Gilliam remade it as the fascinating but inferior Twelve Monkeys.) The latter is a 1983 documentary in which a woman reads letters from a male acquaintance traveling around the world, primarily a sojourn through Japan. What stimulates is not only the kaleidoscope of word and image, but the spiraling number of narrative levels (author, narrator, their perspectives on other cultures as compared to how those cultures see themselves) that make us question what we know to be true.

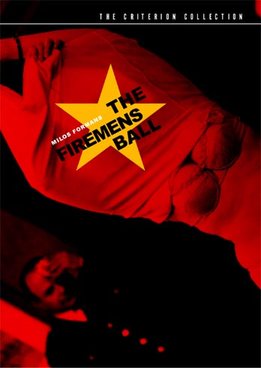

Loves of a Blonde/The Firemen’s Ball: These two brilliant Czech films from 1964 and 1967 are the works of Milos Forman, before the director moved to America and helmed One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Amadeus. The first is a gentle, slice-of-life forerunner to today’s best indie comedies, as a Communist factory girl in a town where women outnumber men 16 to 1 looks for love, the silliness tempered by reflections on the idealism of youth and settling of middle age. The second, starring the real firemen and citizenry of a small town, is one of the most hysterical comedies ever made as everything possible goes horribly wrong at the titular charity event. But we laugh in part to keep from crying, for Forman’s message is that human institutions are corrupt failures, and not even our best-laid and most sincere plans will change that.

Loves of a Blonde/The Firemen’s Ball: These two brilliant Czech films from 1964 and 1967 are the works of Milos Forman, before the director moved to America and helmed One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Amadeus. The first is a gentle, slice-of-life forerunner to today’s best indie comedies, as a Communist factory girl in a town where women outnumber men 16 to 1 looks for love, the silliness tempered by reflections on the idealism of youth and settling of middle age. The second, starring the real firemen and citizenry of a small town, is one of the most hysterical comedies ever made as everything possible goes horribly wrong at the titular charity event. But we laugh in part to keep from crying, for Forman’s message is that human institutions are corrupt failures, and not even our best-laid and most sincere plans will change that.

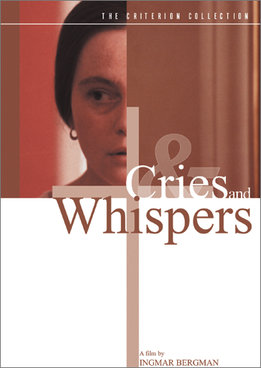

Cries and Whispers: The professor of my freshman year Intro to Media Production class described Ingmar Bergman’s Oscar-winning 1972 picture as “a complete film school in 90 minutes.” Indeed, this simple story of three sisters, whose lifelong dramas come to a climax when one enters the final stage of cancer, is immaculate in terms of cinematography, editing, and production design—a guide for how much can be done without a large budget. But the technical skill only heightens the emotional power to a degree only few movies have reached. We see our own families, our own loves, our own problems in Bergman’s sisters. Thus when the action is heightened with the force of lightning in a whirlwind, we react, and I choose that verb with care: every time I watch this film, my entire body trembles, jerks, loses control to the influence of what is being conveyed on the screen. No other film has ever done this to me, and you can take this as the highest recommendation.

Cries and Whispers: The professor of my freshman year Intro to Media Production class described Ingmar Bergman’s Oscar-winning 1972 picture as “a complete film school in 90 minutes.” Indeed, this simple story of three sisters, whose lifelong dramas come to a climax when one enters the final stage of cancer, is immaculate in terms of cinematography, editing, and production design—a guide for how much can be done without a large budget. But the technical skill only heightens the emotional power to a degree only few movies have reached. We see our own families, our own loves, our own problems in Bergman’s sisters. Thus when the action is heightened with the force of lightning in a whirlwind, we react, and I choose that verb with care: every time I watch this film, my entire body trembles, jerks, loses control to the influence of what is being conveyed on the screen. No other film has ever done this to me, and you can take this as the highest recommendation.

All pictures taken from www.criterion.com

Great start! I’ll look forward to all the entries.