Andrew Rostan was a film student before he realized that making comics was his horrible destiny, and he’s never shaken his love of cinema. Every two weeks, he’ll opine on current pictures or important movies from the past.

Two of the finest documentaries released this year concern themselves with the power to believe, which is crucial to human existence. We believe in things instilled in us after being passed down through generations, and these things, be they faiths or ideologies, help us integrate into society. We also believe in ourselves, which on the one hand is vital to our well-being; self-confidence and finding a worldview that help us deal with existence are important. But it also can be dangerous to if we elevate our ideas too highly, for sometimes they have the power to infect society.

Going Clear: The Pleasure and Pain of Not Thinking

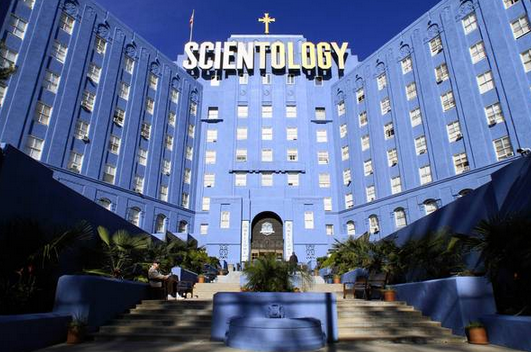

The thesis of Alex Gibney’s film version of Lawrence Wright’s book Going Clear is that one man’s attempt to cope with his own psychological problems led to the formation of a wealthy, powerful, and destructive organization. That man, of course, was L. Ron Hubbard, and the organization is the Church of Scientology.

The thesis of Alex Gibney’s film version of Lawrence Wright’s book Going Clear is that one man’s attempt to cope with his own psychological problems led to the formation of a wealthy, powerful, and destructive organization. That man, of course, was L. Ron Hubbard, and the organization is the Church of Scientology.

Several people close to Hubbard comment in the film that the theory of Dianetics and the core beliefs of Scientology—that human beings can “go clear” by using their mental and emotional faculties to handle stress and negative emotions and achieve self-fulfillment—was his own attempt to handle the stresses and tortures of his life. A fanciful man who wrote pulp sci-fi, served in World War II, and had a taste for sex magick, Hubbard dressed up his ideas in a ridiculous mythology about the evil overlord Xenu, the souls of Thetans, and billion-year-old H-Bomb explosions, and positively rejected psychiatry—a process that put you too much under someone else’s control. Hubbard wanted control, and he set up an institution that incredibly bullied the IRS into making it tax-exempt and bullied its own members by taking their children, paying them forty cents an hour to do menial work, and wrought physical and mental tortures with few parallels.

All of this is carefully documented by Gibney through archival footage and interviews with former Scientologists. Earlier this year, I reviewed the Oscar-winner’s four-hour biography of Frank Sinatra, which was Gibney having a fun break from his serious fare. Here, his directorial mastery is inarguable: he cuts between bright, stark photos and film clips (including the hilarious “We Stand Tall” music video) and interview footage crafted in a clear semi-darkness that accentuates the turmoil of his subjects and throws the Scientology buildings into an eerie light. The editing is impeccable, especially when he weaves some of the scant footage of an ebullient Hubbard talking about the transformative powers of Scientology with that of people who were astounded that his inner circle were basically slave laborers and they were made to physically fight each other in a secret Florida location. Also, Gibney interviews the brilliant and eloquent Wright, but it is the director’s voice that narrates the picture, and the audience feels his increasing incredulity and shock that this scheme wields absolute control over its members and amasses a fortune.

(And on the subject of calling it a scheme, Scientologists respond to the “it’s another religion” remark by pointing out how Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, etc. all tell you up front about their doctrines and beliefs. Scientology gives people Dianetics, makes them spend thousands of dollars on courses and audits, and only then reveals the sacred tenets of Xenu and the Thetans. It is bait-and-switch.)

Going Clear offers stories of John Travolta and Tom Cruise as you would expect, but while riveting, they are not as interesting as the portrait of Hubbard’s successor David Miscavige, who looks like Tom Hiddleston with thirty more years on him. (If Hiddleston used Miscavige as a model for Loki, I would not be surprised.) Miscavige emerges as a power-hungry, Scotch-swilling taker of mental hostages who rips families apart…but also as much a victim, because in the words of his onetime allies, he has to be a true believer because if he looked at what he was doing, it would crumble him with overwhelming guilt.

The depiction of Miscavige and other less well-known but astounding aspects of Scientology are what make Going Clear a compelling watch, alternatively hilarious and horrifying. And Gibney’s best articulator of the bizarre world of Scientology is Paul Haggis, who in a wonderfully frank and moving interview redeems himself for Crash. A longtime Scientologist who left the church when its condemnation of homosexuality (he has two lesbian daughters) led him to investigate its entire dealings, Haggis blasts Scientology—he describes receiving the Xenu scriptures and thinking it had to be a test to see if you were insane—but also describes how it changed his life for the better at first, and above all, how its message of being able to take control of your life through belief is appealing to people who are scared to think for themselves. In these scenes, Haggis and Gibney explain better than ever why people have leapt so quickly at Hubbard’s fragile strands.

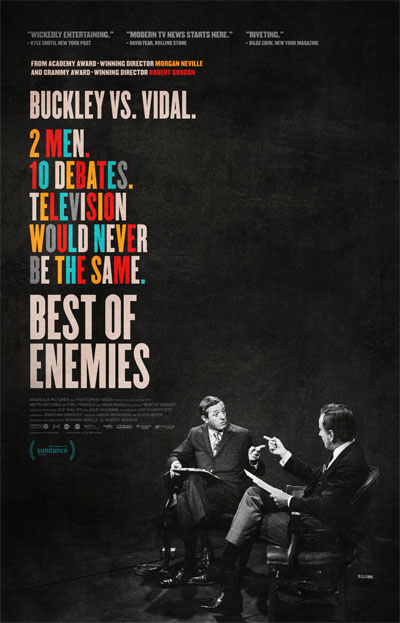

Best of Enemies: A Slap in the Face to the Press

My mother told me once that her grandmother revered Walter Cronkite so much that he could have said the sky was green and she would have believed him. This was not an unusual opinion; Americans treated Cronkite, Chet Huntley, and David Brinkley with the same respect we give Jon Stewart and John Oliver. In a time before soundbites and cable, television news was formal, policy-driven, unopinionated, and extremely dry. Then in 1968, ABC, a distant third in the ratings (their program director laughs that they weren’t fourth only because there was no third network) hit upon an idea for their coverage of the Democrat and Republican conventions: a series of debates to accompany the reporting. Those debates are the subject of the outstanding, fun, and ultimately soul-searching Best of Enemies, directed by Robert Gordon of the Heritage Foundation and Morgan Neville, who won an Oscar for 20 Feet From Stardom. (This is the better film.)

My mother told me once that her grandmother revered Walter Cronkite so much that he could have said the sky was green and she would have believed him. This was not an unusual opinion; Americans treated Cronkite, Chet Huntley, and David Brinkley with the same respect we give Jon Stewart and John Oliver. In a time before soundbites and cable, television news was formal, policy-driven, unopinionated, and extremely dry. Then in 1968, ABC, a distant third in the ratings (their program director laughs that they weren’t fourth only because there was no third network) hit upon an idea for their coverage of the Democrat and Republican conventions: a series of debates to accompany the reporting. Those debates are the subject of the outstanding, fun, and ultimately soul-searching Best of Enemies, directed by Robert Gordon of the Heritage Foundation and Morgan Neville, who won an Oscar for 20 Feet From Stardom. (This is the better film.)

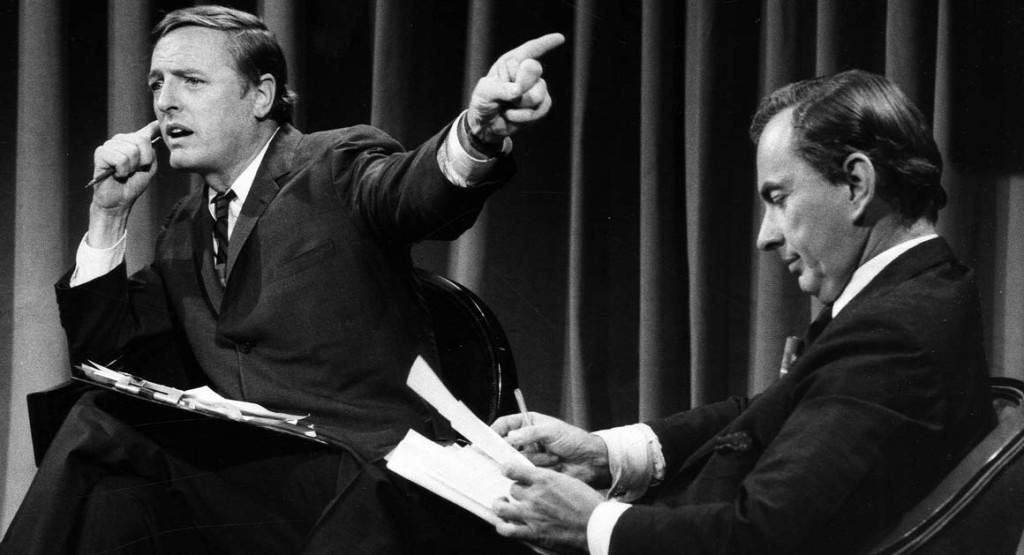

ABC’s two debaters were picked to provoke: National Review founder and Firing Line host William F. Buckley, Jr. and best-selling novelist, essayist, and screenwriter Gore Vidal, who had just published the scandalous Myra Breckenridge. They were men who had a lot in common, including refined airs and failed political campaigns (Buckley had run for mayor of New York City, Vidal for a New York Senate seat), but what they believed in was worlds apart. Buckley was described by his admirers as the Saint Paul of the conservative movement, a man who assembled its many pieces into a cohesive whole and helped Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan find a national audience. Vidal was a liberal not simply of his time but far ahead of it: he recognized the ongoing, revolutionary conflict between police and minorities and insisted that sexual boundaries and classifications were meaningless.

Best of Enemies mixes clips of the actual debates, which became more important to ABC after their entire soundstage collapsed in Miami and their coverage there and in Chicago had to be hastily reassembled, with genuinely insightful interviews by Buckley and Vidal’s friends, biographers, and admirers, as well as excerpts from their letters read by Kelsey Grammer and John Lithgow in some perfect casting. The interviews do a great job at conveying the spirits of both men and of the country in the late sixties, especially one of the final conversations ever filmed with the late, great Christopher Hitchens, clearly ill but lacking none of his insightful power.

The new footage, however, is dull compared to the 1968 debates, a piece of history which I had never been aware of (as I had been with most of She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry). Watching Buckley and Vidal discuss law and order, race relations, and what the future of America should be, the image arose in my head of what this had to have felt like for my parents and grandparents when they were watching. After years of stolid, policy-based newscasting, this was raw, uncensored parrying and thrusting with facts used not as conclusions but as weapons. It is compelling and, up to a point, hilarious, because one of the two major takeaways from Best of Enemies for me was how much I came to be fascinated and repulsed by both Buckley and Vidal. In their torrents of refined but menacing talk punctuated by eye-rolling smirks, Buckley a porcine patrician and Vidal an aging Hollywood leading man, they come across as the greatest models for supervillains one could find. This translates in their debates as them being less interested in conveying truth to their audience than winning over the other. It culminated in the ninth and penultimate broadcast, when Vidal, who had gone through the Grant Park riots with Paul Newman the night before, launched into a tirade and insulted Buckley, who responded “Listen to me you queer, call me a crypto-Nazi one more time and I’ll slap you right in the goddamn face.”

That line still has the power to make you catch your breath in 2015. In 1968 it may have been a nuclear explosion.

The debates would stay with Buckley and Vidal the rest of their lives. Buckley was rendered speechless in a valedictory 1993 broadcast when Ted Koppell showed footage, and Vidal would watch them over and over, Norma Desmond fashion. However, Best of Enemies points out that the debates had a much greater effect on America than either man ever imagined. ABC won the ratings battle and the other networks decided to follow suit by copying their format…setting the stage for the overwhelming partisanship of the media as exemplified by Fox News and MSNBC. The film ends with a series of modern clips of “news” dominated by yelling and slanting, while a TV executive laments “the things that bind us together are the pictures in our heads, and if we’re not seeing the same image, we’re no longer a nation.” The entertaining film is thus, in the end, a work of sadness and warning of how farther split our divided nation could become.

What Hubbard, Buckley, and Vidal have in Common

During the final debate, Gore Vidal made the true, pointed comment that people watching were only seeing a side of him and Buckley and not either man’s whole, but they would accept that this part was the whole. Scientology was not all there was to Hubbard, but it was a part he shrewdly seized on and allowed others to exploit.

Going Clear and Best of Enemies are cautionary tales: we all fall under the sway of the power to believe, but we must be careful of what we believe in and always be ready to question.

Images from All Christian News, The Ambler Theater, Skeptic.com, and Politico. Best of Enemies is in cinemas now. Going Clear is available on HBO’s streaming services.