Andrew Rostan was a film student before he realized that making comics was his horrible destiny, and he’s never shaken his love of cinema. Every two weeks, he’ll opine on current pictures or important movies from the past.

The weather turns cooler, American football begins, and movie theaters transition away from four-quadrant effects-laden corporate blockbusters to more personal visions. The Oscar season begins in earnest, and I’ve often noticed how the first films to get released in the weeks after Labor Day are among the smaller, less sweeping pictures: films more Sundance than Telluride or Toronto and with less appeal for the younger moviegoer. These are movies for grown-ups, built around minutely observed characters and tight dialogue. This week I caught two movies of highly varying quality.

Grandma: The Multigenerational Tale of Our Times

Following the lead of his brother Chris, who stunned audiences with A Better Life four years ago, Paul Weitz steps away from major studio releases with his intimate comedy-drama Grandma. Weitz’s screenplay and direction are well-realized, with almost no mistakes, but this film belongs to Lily Tomlin, for Lily Tomlin is everything in it.

Elle Reid, the protagonist, is an acclaimed feminist poet and professor fresh on the other side of seventy. She has lived a life of righteous anger, principles, and humor, and in the past eighteen months, since the death of her beloved partner Violet, a growing sense of grief and regret manifesting as her most acerbic rage. Then Elle’s high school-aged granddaughter Sage shows up—she’s pregnant, has an appointment for an abortion, but needs the money. Elle dusts off Violet’s vintage Dodge and the two embark on an odyssey through southern California, and along the way Elle confronts her past and present and, like Sage, chooses a future.

There are many great actresses who could have played Elle, but Tomlin inhabits the role as none of them could. She is beautiful in all her age lines and crackling smiles, and she makes Elle’s frequent shifts in mood work through subtle, paced transitions, her voice and movement rising and falling in intensity, her emotions hidden behind a wall of insults and jokes. She doesn’t want them to poke through, but when they do she is forthright and genuinely moving. Most importantly, Tomlin conveys the weight of decades of complex history, success, and failure, her delivery and quiet moments striking at memories the audience comes to understand without seeing. Indeed, the role draws on all of Tomlin’s gifts—the hilarity of Laugh-In and 9 to 5, the emotional depths of Nashville and The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe even the maternalism of The Magic School Bus—and shows them at their best.

Beyond Tomlin’s performance, Grandma succeeds in conveying universal themes through such a simple story. Besides the central tale of emotional maturity, it is startling how much Weitz’s screenplay depicts modern society with both praise and worry. Elle is a mostly-unemployed academic who has only now paid off all her life’s debts. She is frustrated that the battles she and other feminists fought have resulted in Sage not recognizing who Betty Freidan and Simone de Beauvoir are. She can also take pride in how Sage has the ability to terminate an unwanted pregnancy, and the depiction of abortion earns Grandma major kudos. Abortion is treated with seriousness and weight: Sage has second thoughts, talks with earnestness about how she wants a husband and children but not now, and ultimately makes the choice herself without undue pressure. (Though undue pressure results in the film’s finest bit of physical comedy.) And when her doctor describes the procedure to Elle and says “We’re not in the dark ages anymore,” the look on Tomlin’s face says it all about how we could slip back into those dark ages.

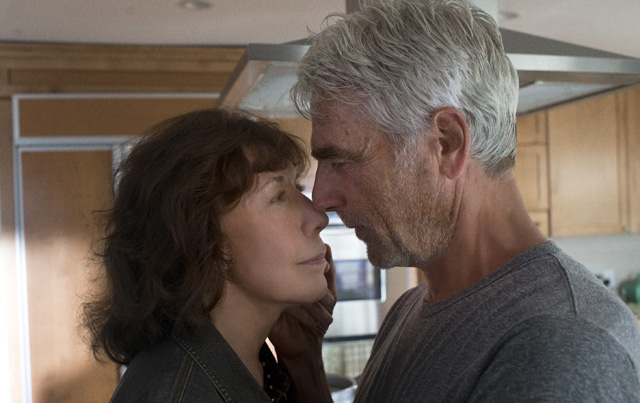

The doctor, by the way, is played by Lauren Tom, one of many terrific actors in the cast. Tomlin spends most of the movie playing off ingénue Julia Garner, who is required to act in a low key as Elle’s foil but hints at a sensitivity that will serve her well in meatier future roles. Most of the film consists of episodes (with chapter titles) in which Sage and Elle encounter various characters. Marcia Gay Harden is the one almost weak link, nearly cartoonish in her Type A shrillness as Elle’s daughter, but Laverne Cox as a tattoo artist friend, Judy Greer as Elle’s adoring and unwilling ex-girlfriend, and John Cho and Nat Wolff in hilarious bit parts are all superb. Then, in a different category, there is Sam Elliott as Elle’s wealthy old flame Karl. A great recent profile of Elliott and his career reinvention in the New York Times gushed over his small role, but words do not do it justice. In ten minutes, Elliott builds an entire existence for Karl, filled with satisfaction, rage, pain, and lovelorn longing, and Tomlin complements him perfectly and pushes him farther. It is a master class in acting and ranks as one of the single best scenes of the decade. If Tomlin and Elliott are not in the Oscar conversation, I will unleash a “Go screw yourself” worthy of Elle at the Academy.

Before We Go: It Looked Good Before I Went

Another, much younger actor trying to show more of what he can do is Chris Evans. I’ve been a Chris Evans fan since the underrated Not Another Teen Movie and today I like how he has both become the heart and soul of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and, unlike some of his colleagues (cough RDJ cough), pushes himself with low-budget movies and ambitious pictures like Snowpiercer. His new movie, Before We Go, sees Evans take his own leap off the helicarrier, as he is the star, producer, and first-time director.

Evans plays Nick, a jazz trumpeter in New York City for the biggest audition of his career, who at 1:30 in the morning randomly encounters Brooke (the fine British actress Alice Eve) when she misses the last train to New England after having her purse stolen. Nick offers to help her retrieve the purse and get home, and the movie is their odyssey through the wee small hours of Manhattan, accompanied by a slow reveal of their pasts and secret desires.

A two-hander is an ideal choice for a novice director, and Evans is competent and, after an introductory shot of him copying Miles Davis’s pose while playing in Grand Central, thankfully ego-free. Evans and Eve are both very charming people who have real chemistry together, especially in a scene where they unwittingly crash a corporate party and have to perform “My Funny Valentine.” And the husband-and-wife cinematographer/production designer team of John and Theresa Guleserian create an after hours New York with hints of danger and moonlit, lived-in loveliness.

All that said, Before We Go is less than mediocre. It took FOUR WRITERS to craft what is basically a long conversation, one of whom was Ron Bass, who wrote Rain Man. This isn’t Rain Man. Nick and Brooke are characters it is so hard to connect with; they spend the duration so concerned with their own intensely personal problems that they seem removed from the rest of the world, and the audience never gets a real chance to step into their existence and empathize. The major emotional beats and speeches happen at random and have awkward timing and dialogue. Moreover, there are supremely bad lines—at one point Brooke says to Nick “You’re the one who’s not facing the music” and I nearly spit out my drink. It may be better to have no lines at all than bad lines, which is good for the supporting cast as almost all of them are forced to play blank clichés. The sole exception is John Cullum, who sparkles as a widowed psychic named Harry in large part because he’s John Cullum. (And yes, Nick and Brooke take time out of what’s nearly a clock movie to talk with a psychic named Harry.)

Comparing this to Grandma is an instructive exercise. In Grandma, cinematographer Tobias Datum does sterling work (a point that Leigh, who I saw the movie with, took particular notice of), creating both an expansive, beautiful Southern California and an inviting, softer mood in the dialogue-driven sequences. Guleserian fails because he moves the camera around far too much in the quieter moments; every time Brooke made a telephone call, I was treated to some of the worst editing I’ve ever seen.

But the final judgment can be summed up like this: Grandma clocked in at 79 minutes and I wished it was longer; I wished I could spend more time in that world. At one point I was sure Before We Go was almost over and I found there were still half of its 95 minutes remaining, and thus settled in to slog it out.

Grandma is currently in cinemas. Before We Go is available on iTunes. Photos taken from Collider, Hollywood Chicago, and the Internet Movie Poster Awards.