Andrew Rostan was a film student before he realized that making comics was his horrible destiny, but he’s never shaken his love of cinema. Every two weeks, he’ll opine on either current pictures or important movies from the past.

In my last column, I put two major Oscar contenders that told the biographies of scientists side by side. This time, I’m comparing movies about painters, which also feature great acting…but further work on every other cinematic level, one of which is among the best of the year.

“Landscape With Distant River and Bay” by Joseph Mallord William Turner…who got a movie about him that’s just as beautiful.

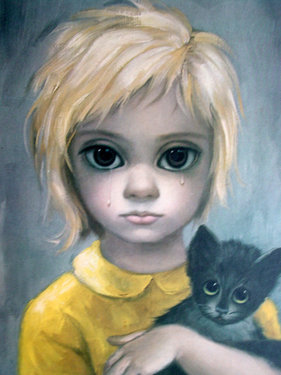

Amy Adams so often plays women possessing and using power in situations, whether with quiet but genuinely frightening terror (The Master) or intelligence and sexuality she wields like weapons (American Hustle), so what fascinates in Tim Burton’s Big Eyes is how she plays a woman who believes she is powerless.

Adams’s Margaret Hawkins Ulbrich is a brilliant artist and a loving, devoted mother, but social politics look down on her as a not-well-educated divorcee, and she feels out of step with the modern culture surrounding her. Fearful of losing custody of her daughter and unable to feel worthy as a painter, Margaret easily falls for the ultimate salesman, Walter Keane, who sells Margaret’s paintings as his own and turns them into an American phenomenon—and turns Margaret into an unknown near-slave, alienated from everyone by keeping her gift secret and falling into despair. That’s the first half. The second is a series of events, some incredibly surprising, that fuel Margaret to slowly but surely discover, claim, and strike out with her own empowerment.

Adams’s Margaret Hawkins Ulbrich is a brilliant artist and a loving, devoted mother, but social politics look down on her as a not-well-educated divorcee, and she feels out of step with the modern culture surrounding her. Fearful of losing custody of her daughter and unable to feel worthy as a painter, Margaret easily falls for the ultimate salesman, Walter Keane, who sells Margaret’s paintings as his own and turns them into an American phenomenon—and turns Margaret into an unknown near-slave, alienated from everyone by keeping her gift secret and falling into despair. That’s the first half. The second is a series of events, some incredibly surprising, that fuel Margaret to slowly but surely discover, claim, and strike out with her own empowerment.

In both halves, Adams excels with one of her greatest performances. She has relatively little dialogue but instead uses her facial expressions and body in overpowering ways; there are many scenes in which simply by arranging her face differently for a few seconds, she makes the audience know exactly what she’s thinking in a more effective way than any monologue. As the film progresses her dialogue remains minimal but her eyes grow sharper, her vocal tone stronger, her body firmer. In standing up to Walter, she grows before our eyes.

Adams’s sparring partner, Christoph Waltz, plays Walter like a hyperactive chameleon ready to charm and persuade or fight back at a moment’s notice; we believe this man could create a national sensation. Like Adams, Waltz ratchets up the intensity through the film, but from such a high beginning, he can only meet Adams’s iron-willed confidence with a little too much melodramatic desperation. In the supporting cast, Danny Huston and Jason Schwartzman are sadly wasted in one-note roles, but Terence Stamp is memorable as the disdainful New York Times art critic John Canaday—his one scene with Adams and Waltz, in which he crushes them both in different ways, is stunning—and Krysten Ritter, with her unusual beauty and flamboyant voice, is a natural for a Burton movie.

Adams’s sparring partner, Christoph Waltz, plays Walter like a hyperactive chameleon ready to charm and persuade or fight back at a moment’s notice; we believe this man could create a national sensation. Like Adams, Waltz ratchets up the intensity through the film, but from such a high beginning, he can only meet Adams’s iron-willed confidence with a little too much melodramatic desperation. In the supporting cast, Danny Huston and Jason Schwartzman are sadly wasted in one-note roles, but Terence Stamp is memorable as the disdainful New York Times art critic John Canaday—his one scene with Adams and Waltz, in which he crushes them both in different ways, is stunning—and Krysten Ritter, with her unusual beauty and flamboyant voice, is a natural for a Burton movie.

I must conclude with Burton. After a decade of huge-budgeted reimaginings and reinventions, Big Eyes feels like the return of an old friend. Burton’s sense of framing and composition has rarely been better, filling the picture with symmetries, color contrasts, and excellent transitions. His one “Tim Burton” moment, a scene where Margaret fully realizes the impact her art is having and sees the entire world as having “big eyes,” works—for that vision marks the start of Margaret gaining empowerment and taking the first steps in her painting away from Walter’s control. Therefore, although Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski’s screenplay doesn’t compare to their masterpieces from the 1990s–Big Eyes is burdened with a too-rushed pace, unnecessary narration, and flat supporting characters–Burton uses his artistry, Colleen Atwood’s realistic yet stylized costume design, Danny Elfman’s jazz combo-meets-strings score, Lana Del Rey’s excellent original songs, and sympathetic direction of Adams and Waltz to carry us over the dead spots.

Of course, it helps when a film has no dead spots whatsoever, and such a film is Mike Leigh’s wondrous Mr. Turner. “Wondrous” is not hyperbole. Leigh’s cinematographer, Dick Pope, creates some of the most indelible, beautiful images I’ve ever seen on film, with sunlight, landscapes, and perspectives interacting in ways that make one feel every single frame is a painting all its own, and more importantly, that we are seeing the world as J. M. W. Turner saw it. It is two and a half hours of sheer beauty that demands an Academy Award and should make Pope be mentioned in the same breath of Deakins and Lubezki.

Of course, it helps when a film has no dead spots whatsoever, and such a film is Mike Leigh’s wondrous Mr. Turner. “Wondrous” is not hyperbole. Leigh’s cinematographer, Dick Pope, creates some of the most indelible, beautiful images I’ve ever seen on film, with sunlight, landscapes, and perspectives interacting in ways that make one feel every single frame is a painting all its own, and more importantly, that we are seeing the world as J. M. W. Turner saw it. It is two and a half hours of sheer beauty that demands an Academy Award and should make Pope be mentioned in the same breath of Deakins and Lubezki.

Pope is one of three behind-the-scenes people who truly make the film. The second is Jacqueline Riding, who receives the unusual-for-the-opening-credits title of researcher. Whatever Riding did was worth every penny. In the construction of sets and attention to detail, the audience never feels that they are watching costumed, made-up actors but living, gritty, sometimes diseased nineteenth century figures who will shave a pig’s head before dinner and then use the same razor to shave their faces.

The third is Leigh, who has long been one of the world’s most assured writer-directors and who now not only masterfully controls the production but also produces a tour-de-force of a screenplay. There is no plot, per se—Mr. Turner progresses through middle-age without a giant exterior conflict—but this is a movie about change, the perpetual, unfailing change all humanity goes through. Turner sees the world shifting and decides he will shift with it through trying new styles of art, finding new relationships, and forming new ideas on how he wants to live and what his legacy will be, all in the face of a world which would prefer he not change. His decisions are not always popular, and sometimes cause him and others great pain, but Turner’s commitment to not staying the same—to continually trying to grow as a person—becomes in Leigh’s hands the most inspiring task anyone could aspire to, becomes the possible and everyday made epic.

In front of the camera, Timothy Spall, who has been wonderful as Wormtail, Winston Churchill, and everyone in between, is extraordinary as Turner. (He won the Best Actor prize at Cannes and that should be the first of many awards.) In the same way Adams can convey a world of emotion in a single look, Spall’s grunts turn almost Shakespearean, and his rough-hewn London accent perfectly mixes with his exuberant, lustful-for-life body to turn his gestures and speech into a living poetry. As compelling as Spall is by himself, his performance stands out all the more in his scenes with others. He is laddish and devoted with his wise father (the wonderfully happy Paul Jesson), terribly misogynist with the devoted housekeeper who lets him sexually abuse her (Dorothy Atkinson), almost unspeakably tender with the widowed boarding house owner who shares an epic romance (the luminous Marion Bailey), full of respect and awe for a brilliant female scientist (Lesley Manville), and ruthlessly mocking to his great admirer John Ruskin, played by Joshua McGuire as the ultimate twit.

In front of the camera, Timothy Spall, who has been wonderful as Wormtail, Winston Churchill, and everyone in between, is extraordinary as Turner. (He won the Best Actor prize at Cannes and that should be the first of many awards.) In the same way Adams can convey a world of emotion in a single look, Spall’s grunts turn almost Shakespearean, and his rough-hewn London accent perfectly mixes with his exuberant, lustful-for-life body to turn his gestures and speech into a living poetry. As compelling as Spall is by himself, his performance stands out all the more in his scenes with others. He is laddish and devoted with his wise father (the wonderfully happy Paul Jesson), terribly misogynist with the devoted housekeeper who lets him sexually abuse her (Dorothy Atkinson), almost unspeakably tender with the widowed boarding house owner who shares an epic romance (the luminous Marion Bailey), full of respect and awe for a brilliant female scientist (Lesley Manville), and ruthlessly mocking to his great admirer John Ruskin, played by Joshua McGuire as the ultimate twit.

In case you couldn’t tell, there’s nothing bad this critic has to say about Mr. Turner. The leisurely pace may deter some, but those who stay the course will see a movie of beauty, exceptional acting, and a message that says a lot about life. Just what you want from a movie.