Pray for Peace

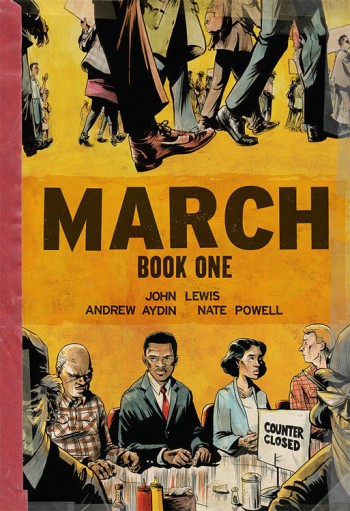

Some of you may have heard of John Lewis, a U.S. Representative for Georgia’s 5th congressional district who—with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and four others—was one of six leaders within civil rights organizations during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960’s. But a lot of younger people may not know his name. Along with Andrew Aydin, Lewis’s Congressional aide, the duo released a graphic novel in 2013 about his fight for racial equality, now stretching over 50 years. While I may not be the first to review this, I thought it relevant to touch upon the importance of John Lewis and his role in a movement that changed the country.

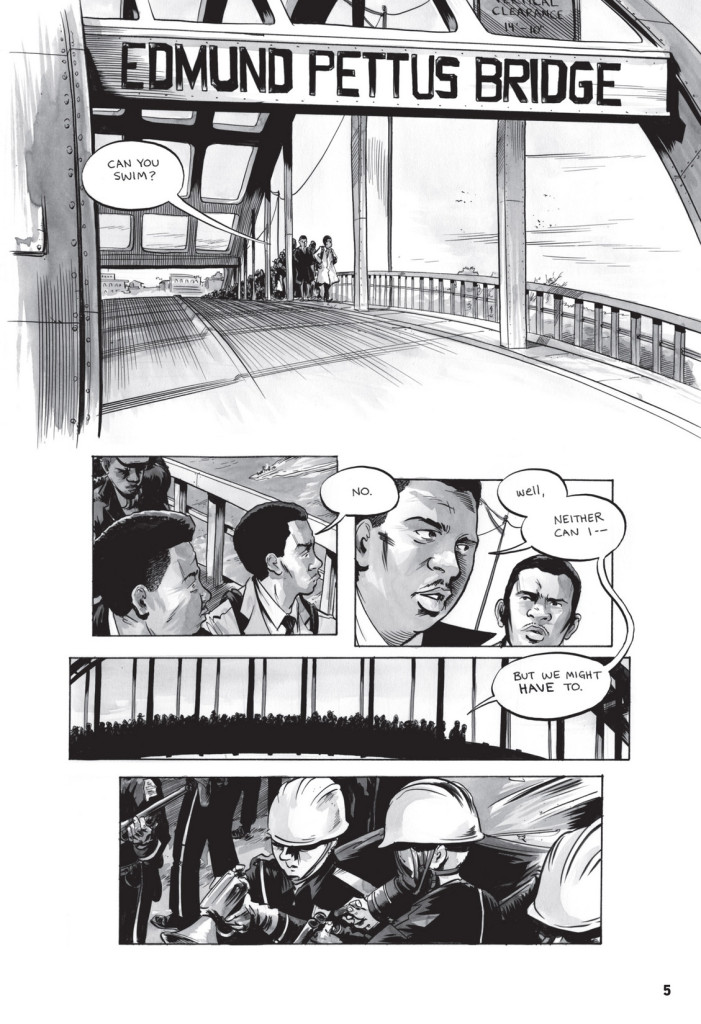

March: Book One begins by tossing the reader right into the action. But this isn’t like the start of a heist film—an impetus that drives the action—it’s just a horrifying recollection of days past. On March 7th, 1965, or Bloody Sunday as it came to be known, John and fellow activist, Hosea Williams, are situated on the Edmund Pettus bridge. Along with a large group of protesters, John and Hosea are told to disperse. The group kneels down to pray as police advance and the beatings begin.

The Trip up North

Artist Nate Powell’s stark black and white style brings not only a reminder of the racial divide in the nation but also stark and beautiful sketches of history in the making. The book flashes forward 44 years to the morning of Barack Obama’s inauguration with a mother and her two sons who come to take a peek at where Lewis works and are surprised to actually find the Congressman present. He invites them in and begins to tell the boys about his past, the farm he grew up on in Alabama, and his love for the resident chickens. Even as a small boy, John was able to tell each chicken apart, giving them names, and building a makeshift incubator for them, as the family could not afford one. Lewis recounts the tragedy of knowing the fate of farm chickens, but still loving them, nonetheless. As his mother reads the Bible to him, John finds power in the words, even if he doesn’t understand their meaning quite yet. He soon learns to read and preaches the gospel to his congregation of resident farm life. It’s clear—even at a young age—that this boy was meant to be a leader.

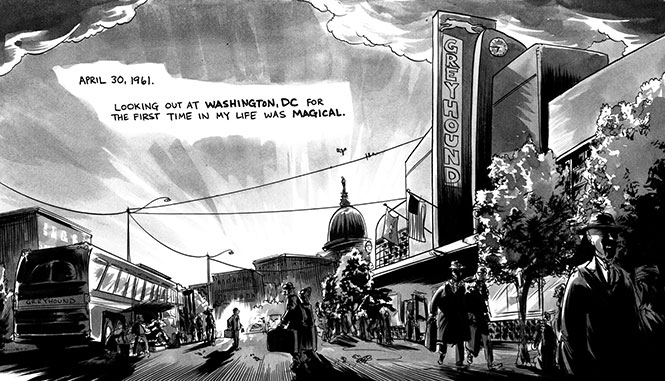

During the summer of 1951, Lewis’s uncle decides to take him on a trip up North. Once they arrive in Buffalo, John sees firsthand how different everything is from where he was raised. His relatives have white neighbors, shop together side by side, and don’t have to raise their own livestock to survive. After his return to Alabama, he devours books in the school library, reads black magazines and newspapers for the first time, and is moved by a speech on the radio by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Call to Action

The Brown vs. The Board of Education of Topeka decision—along with the murder of Emmett Till, Rosa Parks’ refusal to sit in the back of a bus, and Dr. King’s boycott of the buses down in Montgomery—was a defining moment for Lewis in his fight for civil rights and defining himself as a young man. King had inspired in him a fervor to preach a “social gospel” in his own way and Lewis performs his first sermon just days before his sixteenth birthday.

After getting accepted to a seminary in Nashville, Lewis soon becomes restless and decides to apply to a segregated college close to his hometown of Troy. He never hears back but reaches out in a letter to Dr. King. When King wants to meet the “boy from Troy,” Lewis is overwhelmed by the offer to help him file suit against the state of Alabama to attend the school, but ultimately turns him down after his parents decide against it.

This does little to discourage Lewis as he soon returns to Nashville, reinvigorated and ready to become active in the community. He begins attending the non-violence workshops run by Jim Lawson, who was part of a pacifist organization that published a comic book called Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, which mapped out passive resistance as a way to help end segregation.

“This is the Way Out”

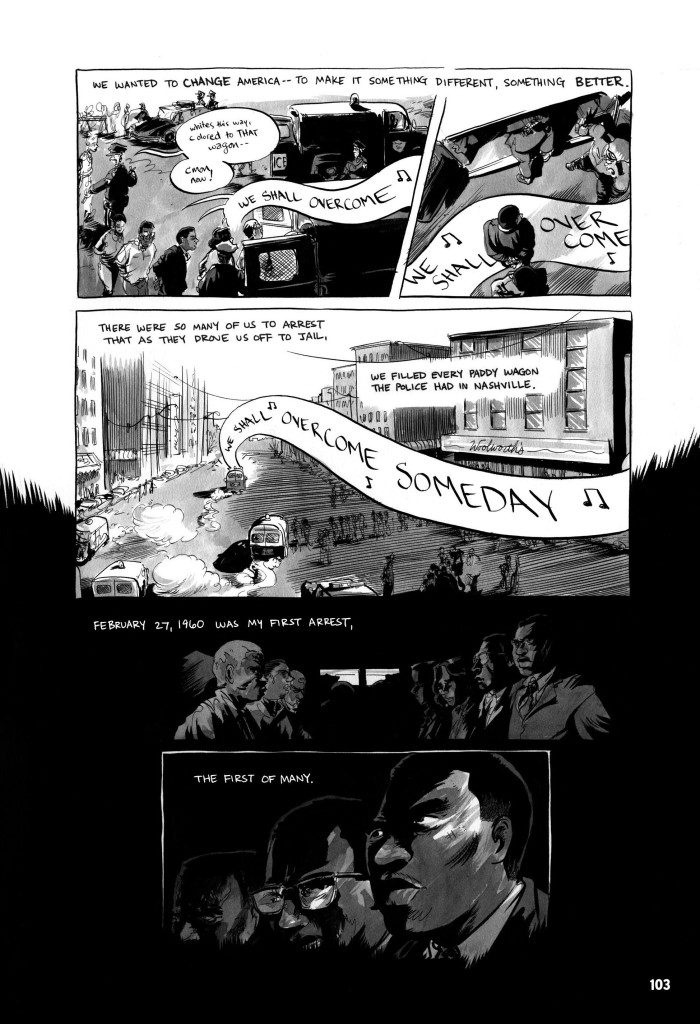

Nonviolent lunch counter sit-ins were soon held in Greensboro and subsequently Nashville. John and his fellow protesters held a sit-in at the Woolworth’s where they were berated, beaten, and arrested but Lewis was not deterred. The Woolworth’s group refused to be fined and were sent to jail for their actions. Leading to the formation of the SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), along with an upheaval in Nashville of store boycotts and irate politicians, the movement that John Lewis helped organize was becoming a very real and tangible thing for the entire country with letters flooding in from the likes of Eleanor Roosevelt and Harry Belafonte.

The bombing of a local black family’s house sparked thousands of people to march on the Tennessee state capitol to demand desegregation of lunch counters and to put a stop to all the violence. On May 10, 1960, the stores of downtown Nashville served food to black customers for the first time ever. They wanted to change America and in this simple, yet nonviolent action, they finally had.

March: Book Two is set to be released on January 20, 2015.