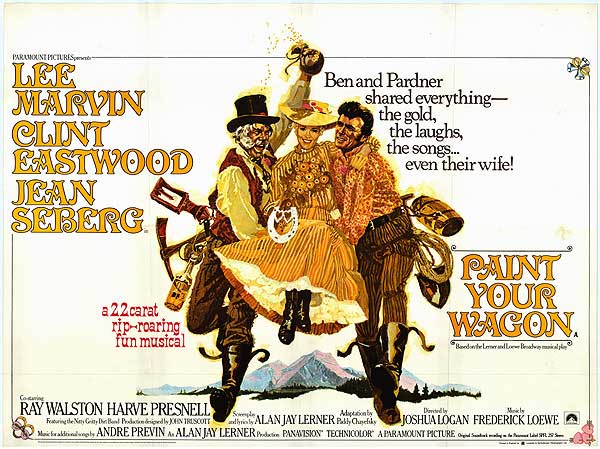

In his remarkably informative and entertaining book Pictures at a Revolution, the story of the 1967 Oscar nominees for Best Picture, Mark Harris devotes several pages to one of the most disastrous gambles Hollywood ever made. After watching West Side Story, My Fair Lady, and the bonanza-grossing The Sound of Music take home the most coveted of Academy Awards, executives at every major studio decided that the public wanted giant, extravagant musicals, films which ran for three hours or so and filled up the Cinemascope screen. The final years of the sixties were littered with big-budget song-and-dance marvels which lost millions upon millions: Doctor Dolittle, Star!, Hello, Dolly!, Paint Your Wagon, Camelot, stretching into the supreme debacle of Lost Horizon.

Since then, Hollywood and Broadway, which once went hand in hand, have been very wary of each other.

There are exceptions to every rule of course, and one exception we would like to single out is Columbia Pictures’ 1968 roll of the dice on Lionel Bart’s adaptation of Charles Dickens, Oliver! Unlike the titles mentioned above, Oliver! achieved both lucrative financial returns and critical acclaim—even Pauline Kael’s review was full of praise, and forty-four years later it isn’t hard to see why. A creative team led by director Sir Carol Reed (who gave us the gift of The Third Man) recognized from the beginning that the air of unreality which makes musicals work on stage, the imaginative factor which allows the audience to fill in the gaps of what isn’t there (and with that imagination accept a world in which people randomly break into song), does not translate to film, a medium which allows for plenty of imagination but also is supremely literal, forcing the audience to see what only the eye of the camera sees. Reed and company thus reinvented Oliver! for the movies, rewriting the script, tinkering with character emphases, and figuring out which songs should be intimately staged and which could be filled out into production numbers with flair and screen-filling technical work. They were ready to alter the work in order to produce a version that could work as a movie and take advantages of the possibilities of film.

I’m dwelling on Oliver! because it was one of two major inspirations for a French composing duo who conceived a giant project in the early 1980s. The duo was Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schonberg, and their other inspiration was the novel which they decided to adapt in the same way Bart adapted Dickens, Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables. Somehow, with the assist of translator Herbert Kretzmer, Bobulil and Schonberg transformed a thousand-plus page novel into a three-hour through-sung musical with some of the most powerful and moving songs ever written for theatre, a show still playing over twenty-five years after its premiere to sell-out crowds in London, New York, and the world at large. Les Miserables is no longer a staid nineteenth-century novel or an ambitious musical. It is a phenomenon, a saga various major studios spent two decades trying to film.

And now there is a film version, a gigantically-scaled film version from Universal which we wrote about back in June, a film version in which director Tom Hooper ignores everything Reed did with Oliver! and further ignores everything we as cinemagoers have come to expect after the innovations of the French and British New Waves, Italy, Hong Kong, Japan, and the American 1970s. Hooper’s Les Miserables pretends all of this never happened, and it almost reaches the level of total fiasco because of it.

For those who read our original article, we at the Recorder had doubts about Tom Hooper as the suitable person to film Les Miserables. He is an unimaginative filmmaker who has succeeded by picking excellent stories and getting the very best out of his actors—as in the extraordinary John Adams and the nearly-as-superb The King’s Speech—and the trailer suggested a film full of pretty locations and a more-than-talented cast to make up for static shots and dull editing. This combination could still have produced a good film, but the result was even worse than imagined.

Possible theory: Hooper knew he was dealing with a supremely melodramatic piece of theatre with a massive fan community who would rip him to shreds for excessively altering anything. And in analyzing Les Miserables as the opera it is, he came to the conclusion that it was the songs and those singing them which made the whole thing work: when I see Les Miserables on stage, for instance, I ignore the torches and barricades and big effects. What keeps me enthralled is how the actors move and sing and connect with the audience through their presence alone. Hooper chose to seize on this and exploit it, to try to recreate the feeling of watching someone sing these songs live. For most of the duration, his screen is filled with their bodies and heads singing the songs in tightly confined spaces, with a rule of only one actor per shot whenever possible.

Like this shot, which NEVER APPEARS IN THE MOVIE EVEN THOUGH IT WOULD HAVE BEEN PERFECT FOR THIS NUMBER because, oh, we have two major characters singing at once and not fighting each other with swords and clubs while doing it!

This is indeed crucial to the musical’s success, but it isn’t the only thing. The greatest collection of songs in the world will not fulfill their purpose unless the audience is also aware of the story behind them and the atmosphere created by the story that drives them along. Hooper, by choosing to favor the actors so overwhelmingly, completely neglects these latter factors…and he does so while not only staying very faithful to the show (all but one honestly unnecessary song was kept in the film) but also adding more details from Hugo’s novel which were not in the show along with giant action sequences, which are nonetheless shot with the same static camera and nonexistent editing as he holds every shot as long as possible and then some.

In this mixture of emotive, close-up performances and overwrought, point-hold-and-shoot production numbers, Hooper has basically taken us back to that late 1960s era of plodding cinematic transcripts of Broadway hits which ignored the possibilities of what the medium could bring and shied away from any notion of reinvention or alteration. Further, Hooper using this style on Les Miserables compounds the situation, because in presenting this hyper-stylized and emotional grand opera as it was, then juicing it up even more with ships dragged through the waves in a way Werner Herzog would have found boring and unnecessary chase scenes and uberviolent deaths, the one dirty little secret of Les Miserables becomes clear.

Admirable as their efforts were in condensing Hugo, Boublil and Schonberg were still smashing 1,000+ complex pages into a bunch of songs with little context for anyone who isn’t familiar with the story and the characters reduced to one-note figures with very simple arcs. On stage, the combination of intimacy and imagination allows this to be overlooked, allows us to suspend our disbelief. But in the movie, Hooper leaves nothing to our imagination, and tries his darndest to simulate intimacy through his extreme close-ups, only one cannot simply put a camera right next to a person’s body and decide that this moving image equals intimacy. This failure makes us fall back on the story and characters and forces us to consider what disbelief we’re suspending. And the consideration can easily leave the feeling that caring so immensely about the travails of someone we were introduced to just ten minutes ago and who is now opening their mouth wide and making elaborate faces at us isn’t worth the investment.

And yet…

I can’t call Les Miserables a bad movie because despite Hooper’s old-fashioned botching of the production, there are two major points in its favor. First, Boublil and Schonberg wrote arguably the most consistently excellent score in the history of musicals, a series of rises, falls, recurring themes, grand anthems, love songs, even a comic number or two, all with unforgettable melodies…I have had practically the whole show in my head since seeing it for the first time nine years ago. And more importantly, the songs make up for the 200 mph pace of the storytelling by perfectly capturing how the singers are feeling about whatever just got explained in two quick minutes of recitative and action. Fantine’s descent into hell may be narrated in one ironically jaunty spitfire number, but “I Dreamed a Dream” captures the truth of that descent, the feeling of having grasped at something and lost everything. The entire show is full of moments just as strong and just as affecting, at least for this writer, who turns into a blubbering mess four-to-seven-times per watching.

And second, Hooper assembled a near-perfect cast and let them go on this dream material, the glaring exception being Russell Crowe. On the scale of actors who don’t really sing, Crowe is no Rex Harrison (but who is) and isn’t even his spiritual brother in “hard living tough guy with a heart of goldism” Richard Harris, who could at least emote his way through “MacArthur Park” with gusto. Crowe, in contrast, sounds like he’s been drafted to take over an alternative rock band from 1992 with his deep, snapping, growling baritone. This isn’t a bad way of singing, but it’s not what is needed for Javert. Javert demands the kind of actor who could play Emile in South Pacific, someone with a rich, melodic tone, while Crowe barely raises his pitch for “Stars” and substitutes yelling for genuine crescendo in “Confrontation.”

Thankfully, Hugh Jackman is a superb Valjean, commanding, tortured, able to hit the high and difficult notes, and projecting sincerity…the apex of my tearfulness in the movie came during “Bring Him Home,” which Jackman delivers with such tenderness and power that the song stops being about one person he only realized existed the day before and becomes a universal prayer.

Amanda Seyfried, stuck in the most thankless and bland role, merely needs to look wide-eyed and pretty while trilling, but her “In My Life” is the best I’ve ever heard from any Cosette. Eddie Redmayne in looks and voice recalls Cliff Richard, a terrific model for the idealistic and lovelorn Marius, and from there delivers a solid…

along with Aaron Tveit as a Roger Daltrey-esque Enjorlas.

Sacha Baron Cohen and Helena Bonham Carter make “Master of the House” the one bright spot it needs to be with cutting music hall theatricality.

And Samantha Banks excels as much as Jackman: her Eponine is a bit sexy and a great deal earnestly soul-bearing, and she gives “On My Own” the perfect, bravura treatment it deserves.

In the end, and this is nothing surprising by now, all of them are overshadowed by Anne Hathaway. Fantine lives an entire novel by someone not Victor Hugo’s worth of plot in twenty minutes, but Hathaway never succumbs to the temptation to overact in the face of raging pathos. She yells, cries, loses her hair and her teeth and her pride, and doesn’t push the moments any more than she has to. And when she sings “I Dreamed a Dream,” well…this writer went from being entranced by her voice to thinking Hooper was being really, really boring on this one to realizing the camera wasn’t moving and Hathaway was giving a definitive performance in one take and all but passing out from tears and admiration right there.

So if you can ignore Tom Hooper’s relentless string of bad filmmaking choices, Russell Crowe’s bad singing, characters who never get any names or backstories, major setpieces which are never fully explained (the second half is almost entirely treated as class warfare pure and simple), a tepid “One Day More” (!!! HOW do you make that tepid? When they ripped it to shreds in South Park: Bigger, Longer, and Uncut it was more exciting than this!) which gets moved to AFTER “On My Own” (!!!!!), and one of the most contrived romances in any musical ever. (Marius and Cosette, you get some darn good songs but you two rush things as much as Romeo and Juliet), you have songs without compare sung by mostly excellent actors giving their all. That’s worth something.

How much it will be worth in the end is another story. For as I write this, Les Miserables is opening to excellent numbers at the box office, and with the Oscars coming up, it’s worth remembering that its great inspiration-turned-heavily ignored good example Oliver! rode a similar path all the way to Best Picture.