How Does This Hold Up? is a series where Alex and a guest check out a movie they haven’t seen in ages or that they’ve always been meaning to watch. They’ll compare the experience of watching these movies now to when they first saw or heard of them and explore the differences there-in.

How Does This Hold Up? is a series where Alex and a guest check out a movie they haven’t seen in ages or that they’ve always been meaning to watch. They’ll compare the experience of watching these movies now to when they first saw or heard of them and explore the differences there-in.

Bean: So I’m starting of this column with my former roommate and our esteemed Editor-in-Chief, Travis Cook, as my guest. We went through the Film Studies program at Bowling Green together, but have enough separations in our movie taste to make for good sparring partners. That’s the idea anyway.

So, we’re starting with a weighty one, Travis. Lost in Translation was a really important movie for me in high school. It came out in 2003, when I was a Junior on the cusp of having to figure out what my post-high school was going to be. So, looking back, I’m guessing that I cottoned to this movie because its story about a young woman and a middle-aged man forging a connection in the midst of existential crises felt familiar.

In related news, I must have been a very weird high schooler. So what was your relationship with Lost in Translation back in the day?

Travis: I came to it in the middle of Lord of the Rings fever, so when I went and saw it, I was scooping out the competition that Return of the King would face at the 2003 Oscars. We talked about this as we watched the movie, but I was in a much different place in that time than the one I find myself in now. At the time, I saw a movie that looked as mature and intelligent as anything I’d ever seen. Here was a movie weighted with great things, a movie that spoke to our generation at large.

Travis: I came to it in the middle of Lord of the Rings fever, so when I went and saw it, I was scooping out the competition that Return of the King would face at the 2003 Oscars. We talked about this as we watched the movie, but I was in a much different place in that time than the one I find myself in now. At the time, I saw a movie that looked as mature and intelligent as anything I’d ever seen. Here was a movie weighted with great things, a movie that spoke to our generation at large.

And it either went completely over my head or I just couldn’t appreciate it, because it seemed like every quiet indie movie that I hated then but love now. (i.e. Her, Eternal Sunshine, etc.) I didn’t hate it, exactly – but I definitely couldn’t see what the fuss what. In my head, Bill Murray was the guy from Caddyshack and Ghostbusters and Groundhog Day, an actor in the middle of the…Murraysance? that turned him into the counter-culture actor/icon he is today.

(Scar-Jo, though…that opening shot is the stuff that the dreams of 16 year old boys are made of.)

So at the time, it was the king of the alt-indie auteur movement started in the early 90’s, a sort of ‘crest of the wave’ kind of thing. (At least, that’s what I remember from the Internet blogs of the period…) And now…well, this movie meant more to you. What was your big takeaway 12 years later?

Alex: So, the biggest thing that surprised me upon watching this for the first time since 2008 (or so) is that I had forgotten how small-scale this movie is. Like you mentioned, it’s a quiet movie and has fairly low stakes throughout. Part of that, which was not something I would have thought of 12 years ago, is that both Murray’s Bob Harris and Johansson’s Charlotte are very privileged characters. He is an aging movie star and she grew up in New York and studied Philosophy at Princeton. So their ennui and disconnection is part and parcel of being the idle rich, which seems to be Sofia Coppola’s overall focus across her career. In her hands their problems take on an esoteric quality that reads as either universal or risible depending on your perspective about “first-world problems.” (Insert a rant from Chris Walsh here)

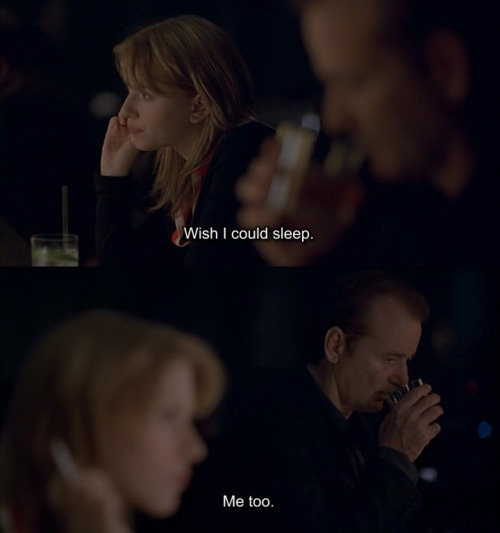

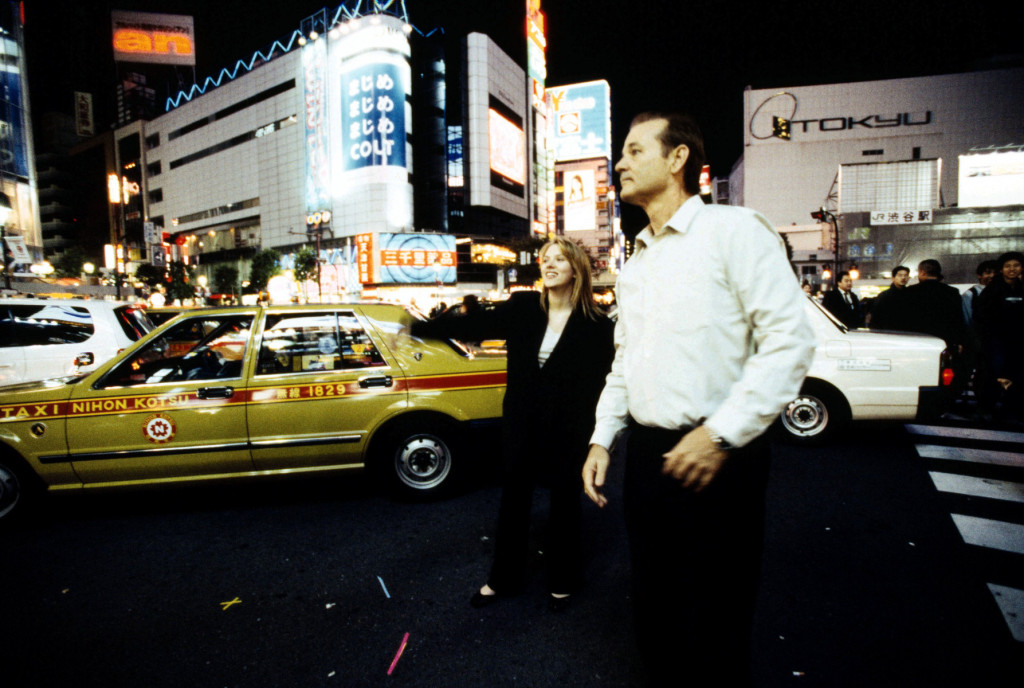

What makes Lost in Translation so interesting as a movie (and a minor cultural phenomenon) is that Coppola mostly refrains from pushing her characters or story to be something bigger or say something important. The characters don’t even cross paths until a third of the movie has passed. Even when the plot does kick into gear, the usual tropes of a meet-cute and whirlwind romance are avoided. It’s just little parties and hang outs and talking until near dawn as two lonely and depressed people find some solace. It’s most overtly appealing thing, outside of the performances from Murray and Johansson, is the way Tokyo is filmed. Coppola and her cinematography Lance Accord used high-speed film and handheld cameras to capture Tokyo’s chaotic and vibrant lights and landscapes. It’s one of those movies where you can say the substance is in the style, much like the cinema of Wong Kar-Wai that inspired them. It still feels very modern for a movie made nearly 15 years ago, too.

But even with that this was unusually low-key film to be such a success. Where was the weirdness or unexpected violence? The twee stylization? The outre political or social satire? It’s remarkable that a tiny movie that lacked those calling cards was able to make $45 million and win a major Oscar. It’s so much the antithesis of what most audiences demand that more than anything I am surprised by its success. It can’t all have been weirdo 16-year-olds like me, right?

Travis: It really does retain a sense of action through inaction throughout the story. In the hands of lesser actors, I really feel like this story would suffer. Part of what makes it work, though, is the natural charisma of the leads. Bill Murray has seldom been finer (Rushmore flashes to immediate memory). In the role of Bob Harris, he portrays a man reaching not some kind of mid-life crisis so much as a mid-life malaise, shilling Japanese whiskey for an easy $2 million. Scarlett Johansson doesn’t carry herself like the 17 year old she was when this movie was released – her natural gravity and vocal tenor bears the weight of someone twice her age.

And yet, while it works, it still seems – I don’t know if forced is the right word. Perhaps too finely sculpted? Coppola pushes the sense of alienation felt by both characters very early on, making sure that the audience sees that these characters “stand out” from their surroundings, and that they “don’t fit in”. It’s effective – the kind of stuff an Intro to Film class should lap up when writing theme papers – but heavy-handed at times. Such efforts come off as too overt, too much of an artistic statement for me to take it seriously. One year later, Richard Linklater told a similar story with Before Sunset, a beautiful movie about the realization that not everything in life is as grand as we hope it will be when we’re young. LiT is a different story, sure, but Before Sunset holds up infinitely better in my mind.

How about you? Does LiT hold up for you? As a film, it’s still damn good, but I probably won’t be burning the midnight oil until I can watch this film again. (Might be another twelve year wait for me…)

Alex: I think that it does hold up, yeah. It’s not inspiring any mania in me circa 2015, but that was more a relic of getting caught up in the annual Oscar race for the first time and trying on that particular cinephile hipster stance back in 2003. Lost in Translation was a movie that helped me figure out who I was back in the day. It expressed the feelings of disaffection and uncertainty that defined much of high school, but in a format that was both funny and beguiling. Weird as it looks in hindsight, it was the right movie at the right time for that particular version of me.

I agree that it’s not perfect, not nearly. It does try too hard to make Bob and Charlotte feel out of place, and its depiction of the people and culture of Japan veers uncomfortably close to racism (Another Walsh rant goes here). But it features the first full blossoming of Sofia Coppola’s dreamy visual aesthetic and succeeds in expressing a very particular feeling with grace and a healthy dose of wit.

The Verdict: It Holds Up Well