According to our records, this will be the 100th post on the Addison Recorder. Hard to believe we’ve done so much since that night in Julius Meinl when Travis concocted this idea.

Speaking of “we,” I’m almost positive that we, like so many of our friends and loved ones in our age group, spent the past week glued to televisions, web sites, and above all a startlingly dynamic Twitter to mourn, follow, and ultimately rejoice over the tumultuous week in Boston. A piece on just how much Twitter replaced media as our major source of information and our shaper of reactions may be due once we have a little more time and distance. But during the entire week, as I was doing all of the above actions with tears and laughter alike, the most significant rush of memories came about what that city means to me.

I went to Emerson College to study film, with a bit of writing and philosophy, and lived in Boston from 2003 to the very end of 2006. For the last two of those years, including the summer of ’06, Boylston Street was actually my home; I lived at the beaux-arts Little Building, the main Emerson dormitory, on the corner of Boylston and Tremont, right next to Boston Common, the Green Line stop, a CVS and a 7-11, a Dunkin’ Donuts (though that’s not surprising since there’s one on every corner), a little Chinese restaurant which had the best Crab Rangoon you could ask for, a magnificent dive of a New York style pizza establishment, and a Loew’s multiplex.

Even on Newbury Street, the fanciest in town…they use how many Dunkin’ Donuts are here to stump people on tour buses.

In short, everything a college student needed. Especially a slightly withdrawn college student trying to absorb everything he could in terms of art and culture, trying to learn from the masters of every art.

When I think about my cultural experiences in Boston, I can tie them to the one thing I never liked about the city…apart from the hellish driving conditions which put Los Angeles to shame on the “best” days. I came to Boston from a town where almost everyone was white, Christian, middle-class, mildly conservative, and reasonably straight-laced, maybe a bit repressed. Cheever and Updike territory. Boston was steeped in history but cosmopolitan, small enough to walk from one end to the other but large enough to offer so much I’d never conceived of in Boardman. And when you’re going to a school for arts and communication, you meet everyone of every conceivable stripe, all races, all ethnicities, straight and gay and bi and trans. Although racial tensions can and will bubble in a place founded by Puritans and still populated with the descendants of those who talk only to God, Boston is a welcoming city, so welcoming that political correctness and liberal attitudes are almost as de rigeur as the ideology of Big Brother. They are the law and you cannot transgress, to the point where in some of our classes we were terrified of raising certain opinions which might have come across as illiberal, and I eventually dove headfirst into Paul Johnson’s histories for a while just to even the balance.

But while this attitude can be annoying, it also makes it impossible to hate Boston, because Boston, as I said, is WELCOMING. It embraces art to the fullest and offers anything and everything on its stages, from the tiny black box theatres, including one in the forlorn and terrifying city of Lynn, where I journeyed one stunningly quiet Friday night to watch my friend Paul Brindley act in an experimental play, to the expanse of TD BankNorth Garden, which will always be the Boston Garden to me, where I saw the Celtics, naturally enough, but also the Who, with the Pretenders opening, playing the loudest, wildest, and most passionate of music, including a closing twenty minutes of “You Better You Bet,” “My Generation,” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again” which I will always remember as sheer perfection.

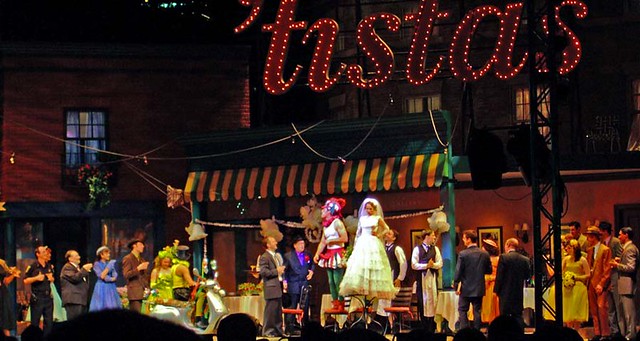

Juxtaposition is nothing irregular in Boston’s arts. This is the city which gave us both two of the greatest orchestras in the country (the BSO and the Pops) and the Dropkick Murphys. (I would imagine that Jonathan Richman, who wrote the single greatest rock song ever by a Bay Stater…sorry Aerosmith…stands right in the center of intellectual refinement and rebellious grit.) This is the city where the MFA, where I saw Monets, Goyas, and John Singer Sargent’s Madame X for the first time in a way which spellbound me, also shows a highly artistic run of the year’s best British commercials every spring. This is the city where people cavort semi-nude and smoke weed on the Common during Patriot’s Day, and that same Common hosts Shakespeare for free every summer. (I saw my first fully professional Shakespeare this way, a delightful reimagining of The Taming of the Shrew keeping all the text but setting it in an Italian restaurant in the 1950s.)

This is the city where colleges charge you to the hilt for textbooks, but the Brattle Book Shop keeps the $1, $3, and $5 racks so fully stocked they’re bursting, and you wander out with two books you weren’t even looking for.

That was how Boston shaped me the most. It introduced me to things I needed which I had never been looking for.

I was 18 when I came and had just turned 22 when I left (And I’ll remember my 21st, my Uncle Tom buying me a fried fish and gingerbread dinner chased down with Guinness, Jameson’s, and Bailey’s.) and I had not been exposed to a lot in my life. I had set ideas in my head not only about how to create art but how people’s lives should be lived.

I got to see two great jazz concerts during my time there. The first was Herbie Hancock performing at Berklee, a two-hour show in which the second half was entirely taken up by “Chameleon” and “Maiden Voyage,” the man squeezing every variation he could from his piano and inventing new ones when he’d run out. The second was Bill Charlap, tinkling the keys with his trio at a fine little club in Cambridge, playing nothing but standards and concluding with a startlingly driven and intimate interpretation of the fiendishly difficult West Side Story themes I had played myself in high school. These concerts–and this sounds pretentious, I know–were the great metaphors for my years there. I entered with a sense of familiarity, went through unexpected revolutions, and ended something new and changed for the better but recognizably, as the jazzman returns to the head after the choruses of solos, the same in foundation.

This especially happened in terms of me and film. Studying the history of film at Emerson and having access to both new movies which could be seen on opening nights and in free previews (I remember walking out of a midnight screening of Peter Jackson’s King Kong at 3 am, into cold wind and snow, feeling sweat pouring out of my brow and ready to run a marathon, of another midnight screening, of Mission: Impossible III this time, the day I auditioned for Jeopardy, and seeing a preview of Eli Roth’s Hostel which I walked out of during the Q&A when I realized my reaction to the film was completely at odds with that of the 700 other people in the cinema.) AND classic movies shown in repertory AND a multitude of books on cinema history changed that. Having a class which showed us everything from Blade Runner to Fallen Angels to Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life to The Flicker was my first eye-opener: after years of nothing but romantic comedies, special effects extravaganzas, and prestige pictures we learned about at Oscar time, I got to see films which fell outside a lot of categories. I read books about grindhouse and exploitation cinema which instilled in me how joyous and liberating it can be to work with minimal resources but tell stories on your own terms.

And for the first time I saw films I loved on the giant screen: 2001: A Space Odyssey, Lawrence of Arabia, Warren Beatty’s own 35 mm print of Reds, Raiders of the Lost Ark, even La Dolce Vita, the latter two at the Brattle in Cambridge, the theatre which sparked the revival of Casablanca, and they reminded me why I wanted to tell stories in the first place, to create a captivating experience unlike any other, for watching and rewatching and seeing them in such detail revealed how nothing one film did was like anything another film did. This experience not only inspired my senior thesis–an extended combined creative work inspired by and meditation on the westerns of Sergio Leone–but also convinced me that yes, I could find my own voice as a creative talent if I worked to develop it. By the end of my time there, I was a storytelling junkie. I read every book I could get my hands on, saw every movie I could see, and grew excited by it all…one night in October 2006 my dear friend Kal and I went to the Harvard Square cinema to watch The Queen and The Departed back to back, and something about seeing the latter in Boston filled us with such vigor that we walked five miles back to our dorm at 10:00 on a not too warm night, barely noticing the journey.

And I gave other people a chance to raise their voices and pack a house. My junior year, I became president of the college film society and curated the only film festival dedicated to Emerson-made work. It was the longest festival in the school’s history: five hours of short documentaries, dramas, surreal fantasies, and humor, made by people with little money and a lot of heart. Some of the talent who made those films are now having their work win awards at larger, professional festivals and screenwriting competitions, and I look back on this experience with pride.

Immersing myself in every kind of film may have helped me transition away from a cinematic career; this time taught me to be open to any kind of art, even that which seemed strange and unfamiliar at first, and eventually I would move out of the realm of movies and find my calling in what seemed a strange and unknowable world then: the world of comics. It helped a bit that my friend Kal’s father drew Superman for years, as well as the X-Men Vs. The Fantastic Four miniseries, so a lot of my neutral state regarding comics disappeared quickly, and I learned the first rules off comic storytelling from exposure to truly excellent DC/Marvel output.

But beyond movies, Boston art changed me as a person.

As I discovered myself away from home and parents and parental rules, one thing I learned quickly was that I am a very emotional person, but those emotions were not a temporary state caused by adolescent wrangling: they were an essential part of my being, a commitment to sentiment and feeling for others. I learned over time not to hide my emotions but embrace them, be open with them to others, and channel them into my storytelling, and that it is an amazing feeling to create art which moves others, that it makes you feel closer to both the art and the people around you. I will always maintain I first learned this lesson through Boston’s musical theatre scene: I remember crying openly during Pippin and breaking down into bawls four times during my first show of Les Miserables and having my friends be very accepting of this.

Boston, again, is an eclectic town. There is one particular semi-animatronic Christmas village which people have gone to for decades, and every Fourth of July the Boston Pops plays on the Esplande with selected guests while fireworks launch over the Charles River and hundreds of thousands of picnickers, people on the bridges, people on boats, thrill to it all. (The year I was there, one of the Pops’ guests was Rockapella, and yes, they sang the “Carmen Sandiego” theme. But the same year I attended both those festive events, I also, encouraged by two friends who were very much into out of the ordinary ways and means, attended a sex expo. Until then, I had been very much under the sway of Catholic education and abstinence teaching in regards to sex, but when a whole group of very friendly people are selling paraphernalia and lecturing on how to have an enjoyable BDSM experience and taking off your female friend’s shirt and bra so she can test body paint…it goes a long way to loosening one up. I’ve never been able to call myself a prude since then.

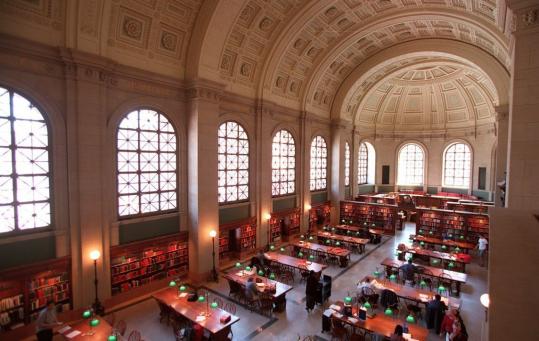

And then, for all those months, rain or shine, I would spend my weekends at the Boston Public Library, writing under the vaulted arch and green-shaded lamps of Bates Hall–my honors seminar papers, my thesis, my first short and long works of fiction and screenwriting. Every time I went to the library, which stands on one end of Copley Square, I walked by Trinity Church, almost 200 years old and a bulwark of Protestantism. I went there once to hear Robert Pinsky lecture on David and another time to hear the great English pop singer Katie Melua perform on the front steps (singing decidedly non-Christian material such as “My Aphrodisiac is You” and Bobbie Gentry’s “Fancy”), but never for services. Then at Easter 2006, depressed at the idea of another gloomy Catholic mass, I decided I should go into the building which was as familiar to me as any block in Boston. By the time the final blessing was given, I had felt more at home, more right, more at peace than I ever had in years. I attended Trinity up until the moment I left Boston, and two years later I was officially received into the Episcopal Church. I don’t talk about my faith on here because, well, that’s not what our site is about! But in this case I need to say that since joining the Anglican side of life, I have become a happier person and written more and better and with a greater confidence, including the essays you read here. And it never would have happened had I not lived on Boylston Street and made the BPL a second home.

That’s why the Marathon bombing shook me up so much; I had walked under the stands, which are built outside the Library, every spring, every year, and always got a bit of a kick out of Patriot’s Day. For someone to turn that into a scene of horror and tragedy was like an insult to every memory I had, an insult to the city’s spirit.

Then I think of the last cultural experience I had before I moved: my father and I across the square, at Trinity for their annual Lessons and Carols service at Christmastime, an ancient building full of young and old, all respectful, joyous, savoring the tradition, singing along with full throats. These people are the sort who would not rest to make their home safe again and who willingly sacrificed to make the final, crucial stages of the investigation and apprehension possible.

Those people will be out in full force this summer, not letting a blade of grass show on the banks of the Charles at the Fourth of July, lining the river on both sides of the path where I used to do seven and a half mile runs, all with an even more riotous but no less genuine spirit of celebration.

Chicago is my home now, and will be for a long time to come, but all of the above is why I love Boston, love what it did for me and my art, love that it made me the sort of person who can write like this.

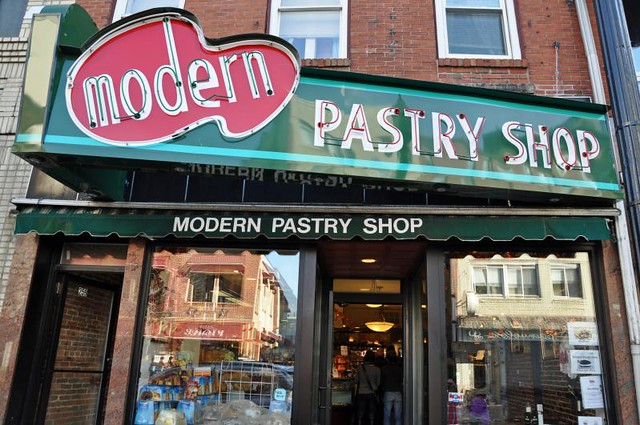

Though if you ever want to find the greatest work of art in Boston, get off the T at Government Center, walk over to Hanover Street, and buy a cannoli with chocolate chips from Modern Pastry. As wonderful as anything in a museum or on a stage.

And anybody who points you towards “Mike’s Pastry” lies. Lies. LIES!!!!!!!!!