My quest to absorb every cultural artifact which piques my interest will occasionally lead to strange convergences. Like the first incredibly depressing night I ever had in Los Angeles, when reading the final chapters of Watchmen coincided with Netflix sending me Requiem for a Dream.

Most recently, on an enlightening and far more positive note, I watched Joss Whedon’s The Avengers.

(This is not going to be a review of The Avengers. There is not much to say regarding the picture except that any group or individual expectations for the film were met or surpassed. One could not have asked for a more perfect extravaganza, 21st-century style.)

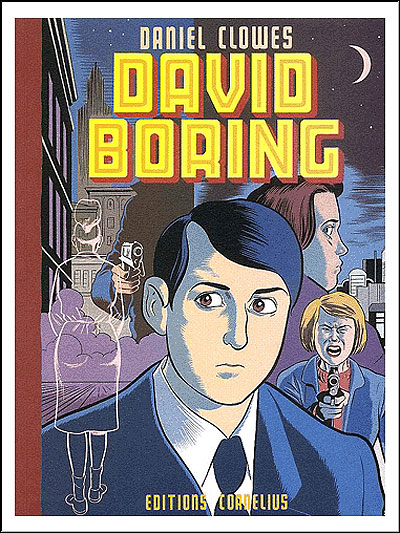

The night before going to the cinema, I finished Daniel Clowes’s 2000 graphic novel David Boring. Written and drawn immediately after his much-revered Ghost World, David Boring is a shorter but denser, more ambitious story, taking on Ghost World’s themes of alienation, aimlessness, and the human desire for emotional commitment from a very different angle. In its medium, it is as much an aesthetic success as The Avengers.

Despite the vast dissimilarity of their works, Clowes and Whedon surprisingly use very similar plot elements, and when considering the novel and film in tandem, a single conclusion is reached.

Yes, there is common ground between Whedon’s retelling of the Avengers’ first assemblage against Loki and his intergalactic forces of chaos and Clowes’s tale of a disaffected twenty-year-old whose only (and surprisingly sincere) desire is to find the one right woman, albeit one who lives up to his fetishistic standards. For starters, both tales are about the potential destruction of the Earth.

David Boring is set against a backdrop of an international conflict which grows more prominent as the story progresses. The nature of the conflict and America’s role in it are never specified, but nuclear and biological warfare are discussed, rumored, and ultimately become reality.

In addition, David’s life is haunted by his father, a comic book writer and artist who walked out on the family when David was small. His father’s name is never mentioned, and the senior Boring’s whereabouts are kept vague for most of the story, but David continually examines the one example he has of his father’s work: a superhero title called The Yellow Streak. Drawn in perfect Silver Age fashion by Clowes, The Yellow Streak’s full-color panels punctuate the black-and-white world of David Boring in unexpected places, but its otherness within the main text extends beyond mere aesthetic treatment.

In Clowes’s conception, the superhero sharply contrasts both our popular conception of a beyond human figure and the “real world” of David Boring as a literally impotent figure. The Yellow Streak, whose name is a connotation for cowardice — a failure to act — is at one point rejected by his girlfriend Florence when she catches him in flagrante delicto with a green-skinned alien with odd appendages. The hero has chosen a figure of uncertain biology, whom he might possible be unable to copulate with, over a person of his own species. The significance of this choice is further brought home when the alien turns out to be the Yellow Streak’s arch-nemesis the Hag in disguise. The Hag is overtly female, with a wild-eyed, hysteric smile of lascivious threat. Her presence suggests a far more sexual nature than that of the Yellow Streak.

This bizarre love triangle (cue up New Order) is only a subplot in a larger Yellow Streak story which is given dramatic pride of place, being on the cover of The Yellow Streak Annual #1 which David holds onto. In the main story, the Yellow Streak’s friend and apparent sidekick Testor Truehand, placed under mind control for a fatal moment, zaps the Yellow Streak into the second dimension. There, without form or substance, the Yellow Streak is unable to perform any deed at all and can only watch helplessly as Testor is besieged by hallucinations. Again, the situation is fraught with sexual undertones. Testor brings to mind testicles, and testicles plus a true, sure hand lead to masturbation and self-pleasure, a sexual act but under conventional morality a regressive and subversive one, which in popular mythology leads to blindness and madness. Deluded by seeing what isn’t really there, Testor is lured to the Hag’s headquarters, thinking he will find the Yellow Streak. Said headquarters are a tall circular tower with a rounded but pointed top, surrounded at its base by black, brambly bushes. The symbolism of the Yellow Streak crying out with futile urgency for Testor to turn away is obvious. Small wonder that when David recalls the one scrap of memory he knows about his father, a charge of obscenity, he thinks of this comic.

The Yellow Streak’s opposite is David Boring himself, who despite his young age is very much in touch with his sexuality. David is promiscuously active and overly particular, judging by a scrapbook full of magazine clippings of women who match his ideal type. But David does not only stand in contrast to the Yellow Streak; the majority of people coming in and out of his life are confused or unrealistic about their sex lives. David Boring is populated with fantasizers in midlife crises lusting over and acting with far younger partners, people who take their ideas on sex from crackpot cultish books, women in relationships with men who slink off for lesbian affairs, horny young men who want to have sex with any woman who moves, and the seemingly asexual who have no interest in sex whatsoever apart from moral disdain.

David is no saint compared to these people in his orbit. His sex drive causes him to sleep with any woman who comes close to matching his profile, and he allows himself to have sex with his mother’s widowed, physically starved cousin, a woman at least twice his age, with unsettling consequences. But all of these sex acts are performed with him clinging to the ideal he never lets go of, and he never hurts or abuses another character or tries to bring his most violent fantasies to life… he genuinely cares for all the women he makes a commitment to, even when such commitments result in pain and suffering for him, including his attempted murder. In spite of his outward demeanor of apathy, David reveals himself to the reader as a someone who has a great, torturing capacity to love, and who expresses that love through a gentle physical sexuality.

By the end of David Boring, David has transformed into something of a superhero, and more importantly, a survivor. He lives through taking a bullet to the head, and in the climax, he has found love and peace while outlasting the increasing destruction of the human race. When one also considers that the person who escapes with him is his best friend Dot, a lesbian whose violent tendencies are countered by her hopeless romanticism and unfailing honesty, Clowes’s message becomes more clear. The superhero, hiding behind costume and mask, is like the “ordinary human” hiding behind their repressions and façades, and who deny themselves the very thing which makes them human, their conscious sexuality. Only the honest people who experience their sexuality with maturity and decision will survive.

I'm not telling you where in the story this is or who she is, but when you know... you might be moved. Or disturbed. Or both.

Clowes’s humanity is echoed by Whedon in The Avengers, and this recognizable connection between we in the audience who obviously have no superpowers and the larger than life figures on the screen. When comparing the members of this “time bomb” of an unexpected family to the other characters in the saga, the six Avengers, like David Boring, share a humanity which everyone else seems to lack.

Examine the Avengers’ enemies and allies. The Chitauri are emotionless drones living only for war, and Loki is shown to only be interested in power and control. There is nothing sexual in his nature, not even his one-on-one confrontation with Black Widow. If Loki does take sensual pleasure in anything, it could only be his urge to dominate others, if the passion he displays when forcing humans to kneel and mocking his opponents is any indication. On the Avengers’ own side, the representatives of SHIELD are sleek and sexless, and the Security Council, despite their obvious power, are as useless and ignored as the Yellow Streak. Perhaps thankfully so, as they intend to launch a nuclear weapon on Manhattan and kill innocent civilians. Since SHIELD themselves, in the person of Nick Fury, admit to wanting to use the Tesseract (the film’s McGuffin) to develop weaponry, every group outside of the titular heroes has their minds focused on destruction, the opposite of the grand result of sex, creation.

The Avengers, who defeat Loki’s schemes and save the world from the further threat of nuclear attack, are all about creation. Throughout the film, they build things and change things and undergo personal changes. Tony Stark builds his massive skyscraper, Bruce Banner can change into the Hulk, Black Widow brings Hawkeye back from mind control, and Captain America takes the most initiative to form the Avengers into a working team. Not coincidentally, Earth’s mightiest heroes also have a grasp on their sexuality.

Tony, despite his penchant for excessive risk and self-destruction, has an established sexual relationship with Pepper by this point, and her serving as his out-of-body conscience spurs him to the most human actions he performs, allowing him to counter Steve Rogers’s impression of him as a thoughtless, flashy jerk. Thor, who genuinely cares about his brother, reveals the extent of his feelings for his beloved Jane Foster in one scene with Phil Coulson, with the implication that he fights just as much to keep her safe as the Earth. Captain America and the Incredible Hulk, though unattached, have romantic histories in their own movies which, like that of Iron Man, serve to remind them of who and what they fight for…indeed, Bruce’s isolation is a result of his unwillingness to hurt those he loves, and it takes coming to empathize with and care for a new group which brings him back into contact with others.

But the main thrust of the Avengers’ humanity, in Whedon’s masterstroke of characterization, lies in Hawkeye and Black Widow. They are the perfect SHIELD agents: unflinching, lethal, trained so well that their lack of superpowers is never a detriment to their becoming part of the Avengers; they’re as excellent as those they assemble with. Theoretically, they should be as cool as Fury, Coulson, and Maria Hill, except for a bond between Natasha Romanoff and Clint Barton which is so strong that she risks her life to save him from Loki’s power, and he in turn listens to her when she pulls him up from his guilt, then saves her during the climactic battle. Whedon never makes the nature of their connection explicit. They could be simply the best of friends, occasional sexual partners, truly in love. But without saying anything, his script and the acting of Scarlett Johansson and Jeremy Renner say everything, that there is an emotional commitment between them which makes each of them stronger and more effective, and that it sets them apart from the rest of SHIELD, pushing them to the heights of the Avengers.

So yes, the Avengers come out alive and ready to eat shawarma partly because they triumph over gods and aliens in the most spectacular action sequence imaginable, but also, like David Boring, they carry a humanity (or learned humanity in the case of the Asgardian) in them which gives them power, conviction, and emotion more than the people whose orders they defy and whose malevolence they defeat.

Daniel Clowes and Joss Whedon have almost nothing in common, but they both believe in the human spirit and the goodness of being in touch with one’s sexuality. And their stories exemplify this in a way we can learn from.

(A final note: Clowes and Whedon’s sexuality is non-discriminatory. Under their paradigm, it doesn’t matter if one is straight, gay, bisexual, practices BDSM, has fetishes, as long as their sexuality is healthy and mature. Abuse, self-punishment without pleasure, and immature non-discrimination are the only sins in their world.)