I love a study in contrasts.

Back in high school English, my class was assigned Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises while another class was tasked with The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Being curious, I asked my teacher why we were not all reading the same novel. He told me that he thought the two books were always paired in his mind, contrasting visions of a generation of Americans adrift after the cataclysm of World War I. He liked teaching both at the same time because the immediate comparison illuminated the strengths and weaknesses of each novel. Hearing this, I raced to the book store and bought a copy of The Great Gatsby so that I might do the same mental exercise as my favorite teacher.

I greatly enjoyed The Sun Also Rises; its terse, direct prose and understated emotion garnered my praise in class discussions when few others came to its defense. In truth though, I barely remember that novel now because it paled next to The Great Gatsby. Gatsby was everything I wanted a novel to be at that time and place. For a junior at an all-boys Catholic high school in suburban Detroit, an exciting life seemed a remote possibility (first-world problems, I know). To read the story of a Midwestern boy like myself, who pulled himself into the highest strata of society in pursuit of a lost love was just perfect. It was wish fulfillment that doubled as a badge of prestige. By identifying myself with poor, doomed Jay Gatsby, I was saying that was the life I wanted.

Not in the particulars necessarily, but in the big, broad symbols and emotions that Fitzgerald embraced and Hemingway kept at arm’s length. I would be that rare, successful somebody who kept his soul locked away from greed and avarice. Maybe I wouldn’t be grasping for a green light at the end of a dock, but something similarly romantic and important would work just as well. The Great Gatsby gave me that dream, that dream of America as a land of endless opportunity, even as it devoured those who dreamed too big.

I tell you all that to preface another study in contrasts, one that may ultimately be just as illuminating about my tastes these days as that Hemingway vs. Fitzgerald showdown was back in high school.

In recent weeks, a slew of teaser trailers have been released for the films that will compete for audiences and awards come the end of the year. Some of them I don’t really care about (maybe another member of the Recorder’s team will tackle Les Mis for all of you?), but two in particular jumped out at me. The first, as you have probably guessed, was for Baz Luhrmann’s remake of the novel about which I just spent 300 words bloviating on about.

The other is for the new film from America’s resident genre deconstructionist, and possibly the only man who can draw fanboys and cinephiles to his new releases in equal droves, Quentin Tarantino. His new film, Django Unchained, is a ‘Southern’ about the titular slave who is promised emancipation for himself and his long-lost wife if he will help a bounty hunter track down a brood of outlaw brothers.

It’s pertinent to point out the similarities of the trailers and the films they represent. The most immediate similarity: Neither of these trailers are representing ‘original’ work. Gatsby is in the canon of Great American Novels, of course, and this film represents its fifth adaptation from page to celluloid. Hollywood has revisited this territory about once a generation, though none of the iterations have been viewed as successful. Clearly, though, this material holds great allure for generations of American readers, judging by its continuous presence in classrooms and academic lists.

Though not a direct adaptation of any particular piece, Django Unchained is similarly indebted to a landmark of American storytelling. Westerns have been functioning as myths and legends in the American psyche since the idea of ‘the West’ was first conceived. Though he has been calling it a ‘Southern’ in deference to its setting in Dixie, Tarantino clearly means for this film to fit right into that cinematically overloaded form. Judging from the trailer, he intends for this film to join those of John Ford, Howard Hawks, Sergio Leone, and Sam Peckinpah in reflecting on the United States’ historical adventures in order to examine its contemporary mores. He is not alone in this, as the past decade has seen something of a revival of the Western after decades of slumber. Artists across multiple media have been creating Westerns have once again found their resonance for both critics and audiences. [SW1]

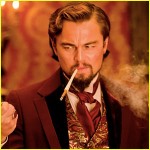

The two films also share a prominent cast member. One of the world’s biggest movie stars and box office draws, Leonardo DiCaprio pays the titular lead in Gatsby while also appearing as an apparently villainous plantation owner in Django. Not being obsessed with the technical aspects of acting or stardom, I regard this mostly as a curiosity. It will be interesting to see how both films market themselves as Christmas approaches, since they open simultaneously. The projects and roles seem distinct enough that I doubt anyone will wind up in the wrong theater, but it will be a conundrum for some studio PR folks.

These two trailers elicited wildly different reactions from me upon their release. When I saw the trailer for Gatsby, my countenance was grim [SW2] and I found myself wincing and sighing throughout the proceedings. Admittedly, I’ve had reservations about this project since it was announced. Baz Luhrmann’s contemporary take on Romeo + Juliet has always held my interest, and I’ve never had a bad time watching Moulin Rouge. But his blazingly bright, frenetic style seemed ill-suited to Gatsby‘s mostly rueful tone. The trailer only confirmed my fears.

From the start, viewers are blasted with images of gaudiness. CGI cityscape shots of party-haven Manhattan in the Roaring Twenties are followed by a chaotic montage of revelers that seems disturbingly similar to the absinthe-fueled opening moments of Moulin Rouge. To be perfectly honest, I probably had flames on the side of my face already. This was not how a trailer for Gatsby should start, not the Gatsby I had held in my head since leaving high school. Instead of being a film about the glorious, romantic strains of American hope and fallibility, I was being presented with a ridiculous fever dream of flashy costumes and anachronistic music. The focus of this trailer seemed to be on the elements of the novel that I had always seen as the sideshow.

Even when the trailer slowed down and introduced the plot, things did not improve. DiCaprio’s Jay Gatsby seemed like the by-now archetypical angry and repressed DiCaprio character, rather than the suave and sophisticated man from the novel. He seemed less like a man who would throw lavish parties every night to lure one particular guest, and more like a man who would sit in the bushes with a pistol waiting for his target to appear. Anyone who took high school English knows how wrong that characterization seems. The rest of the trailer was much of the same turgidly bombastic soap operatics. Tobey Maguire shouts in the rain! Carey Mulligan looks ready to weep at a second’s notice! Wake me when my rage-induced coma is over.

The stark contrast between this trailer and Django could not be more pronounced. Inevitably, the place to start assessing any Tarantino flick is with the man himself. I will admit while I greatly enjoy Tarantino’s work as a director, I am not one of those 20-something cinephiles who worship the ground he walks on and can quote Pulp Fiction ad nauseum. In fact, I think I’ve read The Great Gatsby more recently than I have seen Pulp Fiction. He’s an American master, no doubt, but his films have not meant nearly as much to me as those of his contemporaries like Wes Anderson or Spike Jonze.

Westerns, though, are my weakness. Any film, TV show, video game, novel, or historical book that features men in cowboy hats moving through wide-open spaces has my immediate and undivided attention. I wrote my longest undergraduate research paper and my master’s thesis about contemporary Westerns. My wife would probably swear an oath that I never stopped grinning when we first watched True Grit. Hell, my students could probably swear out many oaths that I never wax more rhapsodic (or waste more time) than when I am introducing a Western during our weekly screenings. Something about the traditions of that genre, its ability to function as both satisfying mass entertainment and rarified cultural mythology speaks to me in ways I don’t entirely understand. Maybe I just need to take more road trips out west, but for whatever reason, that alone had me excited for this project.

All of which leads back to our study in contrasts. If my reaction to The Great Gatsby’s trailer had been frustration and disappointment, then my reaction to Django Unchained‘s trailer was delight and elation. Where Gatsby’s trailer started in a mode of kinetic excitement and overstimulation, Django lets you into its world slowly. The trailer starts with a long (by movie trailer standards) sequence showing a line of manacled slaves being lead across the vast American terrain accompanied by the somber tones of Johnny Cash. We see no faces and hear no voices until Christoph Waltz makes his showy entrance to the proceedings. In short order, we’ve been introduced to Jamie Foxx’s Django, Waltz has dispatched with the slaveholders, and James Brown has come squealing onto the soundtrack. The rest of the trailer is not all that dissimilar to Gatsby‘s; we are introduced to characters (DiCaprio can smile? Sure, he still looks evil, but who knew he could smile anymore?) and plot points, shown some of the more impressive landscapes and action sequences (love that shot of blood spraying over cotton), and sold on the idea of spending two-and-a-half hours on this film.

To be sure, Django’s trailer reflects its creator’s idiosyncratic take on its material just as surely as Gatsby’s did. In a recent interview with the Daily Telegraph, Tarantino has stated that he regards this film as a “spaghetti western set in America’s Deep South” which he called “a southern,” stating that he wanted “to do movies that deal with America’s horrible past with slavery and stuff but do them like spaghetti westerns, not like big issue movies. I want to do them like they’re genre films, but they deal with everything that America has never dealt with because it’s ashamed of it, and other countries don’t really deal with because they don’t feel they have the right to.”

This sort of historical and genre deconstruction seems perfectly in line with both Tarantino’s record as a director and what the Western can do as a genre. His quote about using the film to ” deal with everything that America has never dealt with because it’s ashamed of it” is a perfect statement of the function that genre films have always had in American popular culture. We imbibe an adventure story for its action, thrills, and romance, but there is a deeper level of connection between these films and their audience as well. Westerns perpetually presented the audience with a conflict between the highly valued independence of the cowboy and the necessary orderliness of civilization. In real life, this is an intractable problem, but Westerns present a solution through their violent plot mechanisms. The cowboy can kill or challenge the problem that threatens civilization, thereby symbolically identifying himself with both order and freedom while vanquishing the latter. Sub in the intractable problems of slavery and post-emacipation racism in the South for the issues of order and conquest in the West and we can see what Tarantino is up to.

Why did this trailer work so well while the former made me so unconscionably angry? A lot of it is personal baggage, I’m sure. Django Unchained is not a title that is intrinsically tied to some deep ideas about myself or my self-worth, so it had less of a barrier to leap over there. But Westerns are also heavily loaded material for me. If Tarantino’s trailer had seemed to make a mockery of everything I hold dear in Westerns, as Luhrmann’s did with Gatsby, then my reaction might have been the same. Instead, Django Unchained pulled off the enviable feat of making its film look both fully modern, while still keenly aware of the tradition it’s taking part in.

That’s what was missing in the preview for The Great Gatsby. I got no sense that Luhrmann was treating the material as anything but a silly trifle to be turned into something pretty, fun, and fabulously dramatic. Fitzgerald’s writing can be read that way, to be sure, but to me it always rang with a sense of place and a keen awareness of history more than anything else. That’s what makes the ending of Gatsby so wonderful for me. It’s not the dramatic irony or sadness of Gatsby’s demise and Daisy’s resignation that I remember. It’s the rueful, reflective words of Nick, piecing together the whole picture and seeing the melancholy meaning of it all. Something tells me that moment will be lost in Luhrmann’s translation.

Judging by the trailer, I cannot imagine that Tarantino will lose even a bit of what makes the Western so beautifully alive more than a century after the frontier closed, and decades after the genre had its moment in the sun.

Alas, we will have to wait six months to compare and contrast these two films in full. I cannot wait.